There was an interesting article in the Harvard Business Review, Why People Quit Their Jobs, that provides great analysis on when your team members are most likely to leave. I have written repeatedly on the importance of recruiting a great team, and the logical next step of retaining the great people you have recruited, and one key to retention is understanding when your people are most likely to leave.

Why people leave

Before looking at when people leave, it is important to recap why people leave. Traditionally there are three key reasons people will leave a job they have held for several years:

- They do not like their boss

- They do not see opportunities for promotion or growth

- They get a better opportunity (and often higher compensation

When people leave

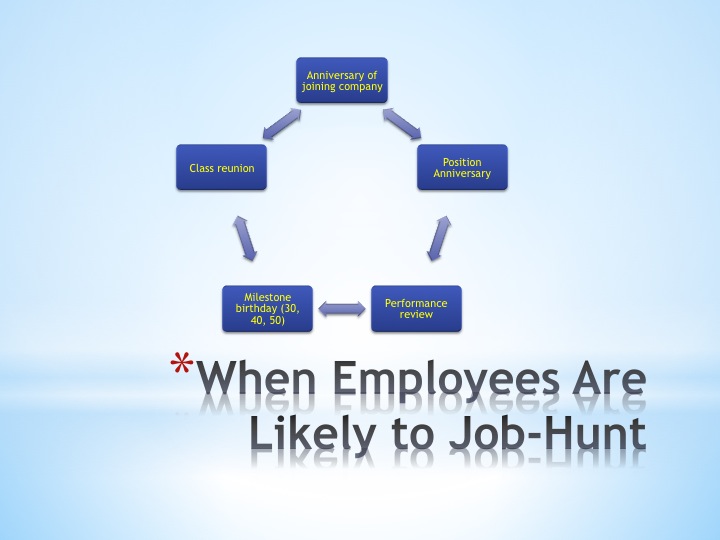

Research cited in the article shows that there are certain events that trigger people to review their situation and thus exacerbates the above reasons people leave. The strongest of these events is work anniversaries, a natural time of reflection on whether joining the company turned out the way the person expected, when job-hunting activity increases 6-9 percent. These anniversaries are not only limited to joining the company but also starting a new role. Also, a formal review is likely to trigger a job search, especially if it does not include a promotion or clear promotion path.

The research also showed there are triggers outside of the company that also prompt heightened job search. Birthdays, particularly milestone birthdays (30, 40, 50, etc.) prompts employees to reflect on their life situation and whether they should pursue a move. School anniversaries serve a similar purpose, as they prompt employees to compare themselves against their classmates. The research shows a 16 percent increase in job-hunting activity after reunions. The key is that events outside of the workplace have a strong impact on whether an employee will be looking for another position.

Other clues to leavers

In addition to the extrinsic and intrinsic factors that trigger job search, there are other ways to identify employees (or teams) more likely to leave. Computer monitoring can identify higher usage of LinkedIn or other job search websites. Tracking employee badges can detect those leaving the office frequently, presumably to interview or speak with recruiters. There are even technology firms that can predict likelihood to leave based on who people are connecting with on LinkedIn.

What you should do

As I wrote, you should always be recruiting your own team to minimize their chance of leaving. Realistically, not everyone has the time or resources to do this so at a minimum you can use the above triggers and hints to focus on those employees when they are most likely to leave. Ensure that you have clear conversations with them their career path in the company, and if they do not have one you should work to create one. Also, encourage your HR team to recruit internal candidates who are likely to be job-hunting for other positions at the company, so if they are going to move they still stay within in the company. Research shows that pre-emptive intervention is much more effective that waiting for someone to get an offer and then making a counter-offer, as 50 percent of those you retain by counter-offer will still leave within twelve months.

Key takeaways

- Retaining employees is important as recruiting them, and understanding when they are likely to start looking for other positions allows you to pre-empt a move

- Employees generally leave because they dislike their boss, do not see opportunities for promotion or growth, or get a better opportunity

- They are most likely to start or increase their job search during work related events (work anniversary, position anniversary, performance review) or life events (major birthday, class reunion, etc.).

In the computer game industry, I believe the biggest impetus to employee departure is their confidence in the company, and the abilities of the management.

JOB SECURITY

Small to mid-size companies in the computer games industry are notoriously volatile. It’s not uncommon for a corporate collapse to leave employees out in the cold, without any severance or back-pay, and frequently with wages still owed to employees. Yes, some of this may be recoverable in court, but former employees have a natural reluctance to ruin references and goodwill to help get another job, just for the chance of receiving a fraction of the money owed years later.

Even if someone has not experienced that, in the computer game industry, members of your team probably know someone who experienced this kind of horror story. The writers of the Harvard Business Review mostly live in a world far, far removed from this kind of “wild west” business environment. Therefore, their studies almost certainly are biased toward employees at companies with greater stability.

I do not have any statistics, but in Maslow’s Hierarchy of Needs, the security and safety of a job trumps issues of esteem or self-actualization. In my 33 years inside the computer games industry, I have repeatedly seen people leave a company because its future is uncertain. Sometimes they get a better position, but in almost every case, they feel their new company gives more job security.

INCOMPETENT AND/OR EXPLOITATIVE MANAGEMENT

The computer game industry has many young, upstart companies. Management expertise and valuing employees may not be in the “Corporate DNA.” Poor leadership and management of human resources is another leading cause of people leaving a computer game company. Many managers don’t explain decisions, don’t appear to listen to their employees, and project after project create weak estimates and plans that repeatedly lead to projects requiring much overtime, as well as going over schedule.

For example, some companies expect that development teams will spend four to six months in “crunch time” (60-80 hour weeks) at the end of a project. Schedules and workloads are built around this implicit assumption. This kind of planning is calculated, crass exploitation, regardless of whether it is conscious or unconscious in management’s mind. When workers see it happening again and again, they recognize it and take action appropriately.

Apparently, this situation is rare enough in the businesses studied by the HBR authors that it became invisible within their study. However, if they their study had concentrated on the employees of EA and Activision over the last 15 years, and compared it to work patterns within those companies, I think a different image would have emerged.

LikeLiked by 1 person