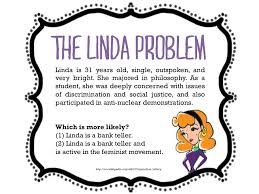

I have written several times about the work of Kahneman and Tversky, highlighted in the book Thinking, Fast and Slow, and how helpful it is in understanding decision-making and consumer behavior. One of the most enlightening experiments done Kahneman and Tversky, the Invisible Gorilla experiment, shows the difference between tasks that require mental focus and those we can do in the background.

The Invisible Gorilla experiment

In this experiment, people were asked to watch a video of two teams playing basketball, one with white shirts versus one with black shirts (click to see Invisible Gorilla experiment). The viewers of the film need to count the number of passes made by members of the white team and ignoring the players wearing black.

This task is difficult and absorbing, forcing participants to focus on the task. Halfway through the video, a gorilla appears, crossing the court, thumps its chest and then continues to move across and off the screen.

The gorilla is in view for nine seconds. Fifty percent, half, of the people viewing the video do not notice anything unusual when asked later (that is, they do not notice the gorilla). It is the counting task, and especially the instruction to ignore the black team, that causes the blindness.

While entertaining, there are several important insights from this experiment

- One important insight is that nobody would miss the gorilla if they were not doing the task. When you are focusing on a mentally challenging task, which can be counting passes or doing math or shooting aliens, you do not notice other actions nor can you focus on them.

- A second insight is we do not realize the limitations we face when focused on one task. People are sure they did not miss the gorilla. As Kahneman writes, “we are bind to our blindness.”

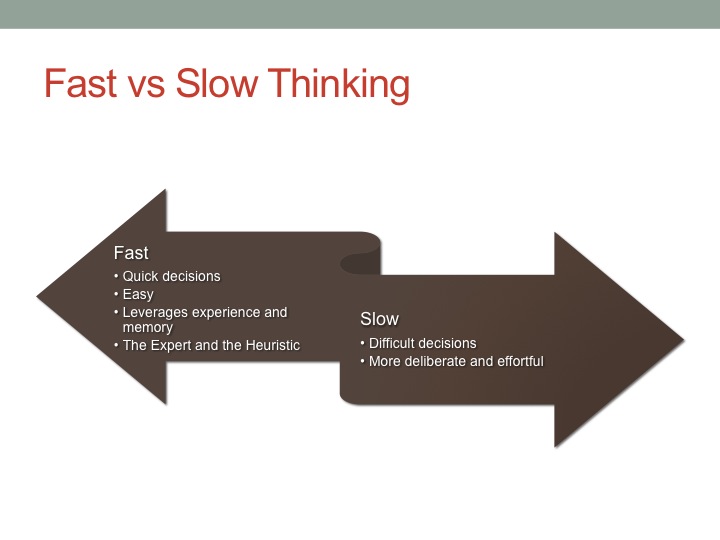

System 1 and System 2

The Invisible Gorilla also serves as a framework to understand the two systems people use to think. System 1 operates automatically and quickly, with liitle or no effort and no sense of voluntary control. An example of System 1 thinking would be taking a shower (for an adult), where you do not even think about what you are doing.

System 2 thinking is deliberate, effortful and orderly, slow thinking. System 2 allocates attention to the effortful mental activities that demand I, including complex computations. The operations of System 2 are often associated with subjective experience of agency, choice, and concentration. The highly diverse operations of System 2 have one feature in common: they require attention and are disrupted when attention is drawn away .

The automatic operation of System 1 generates surprisingly complex patterns of ideas, but only the slower System 2 can construct thoughts in an orderly series of steps.

Implications

Understanding System 1 and System 2 has several implications. First, if you are involved in an activity requiring System 2 thought, do not try to do a second activity requiring System 2 thought. While walking and chewing bubble gum are both System 1 for most people and can be done simultaneously, negotiating a big deal while typing an email are both System 2 and should not be done at the same time.

Second, do not create products that require multiple System 2 actions concurrently. While System 2 is great for getting a player immersed in a game, asking them to do two concurrently will create a poor experience. A third implication is when onboarding someone to your product, only expose them to one System 2 activity at a time.

Example from our world, Urbano’s Failed App

I like to use examples from the game space to illustrate how understanding Kahneman and Tversky’s work can impact your business. In this example, Urbano runs product design for a fast growing app company at the intersection of digital and television. He has built a great sports product that allows players to play a very fun game while watching any sporting activity on television. Unfortunately, Urbano’s company is running out of funds and the next release needs to be a hit or else they will not survive. Although the product has tested well, Urbano is nervous because of the financial situation and decides to add more to the product, to make the app based on what happens the past three minutes during the televised match. They launch the app and although players initially start playing, they never come back and the product fails.

Another company buys the rights to the product and conducts a focus test. They find out users forgot what happened on television because they were focusing on the app and then could not complete the game. They take out the part requiring attention to the televised match and the product is a huge success. The difference was that the latter did not require multiple System 2 thinking simultaneously, it left television watching as a System 1 activity.

Key Takeaways

- In a famous experiment, people watching a basketball game who had to count passes one team made missed the appearance of a gorilla on the video. The experiment showed when you are focusing on something, you do not notice what else is happening.

- We are blind to things in the background. We are blind to our blindness. In the Invisible Gorilla experiment, not only did people not see the gorilla, they refused to believe that they missed a gorilla.

- There are two types of mental activities, System 1 that are automatic and reflexive, and System 2, that requires deliberate, effortful and orderly thinking.