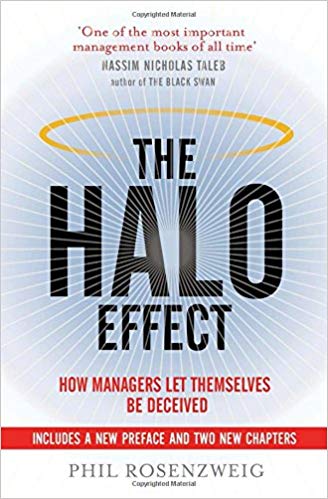

Several months ago, a colleague read and commented on

The Halo Effect by Phil Rosenzweig, and although I have mixed opinions of the book it contains some great lessons on avoiding biases that lead to misjudging the causes of success or failure. Since reading the book, I have extended these ideas to both understand what activities to replicate and how to communicate better cause and effect.

The Halo Effect drives people to over-simplify why a company or product is succeeding, often misattributing it to leadership or a visible initiative. It can lead to negative consequences by driving incorrect hiring and firing decisions or causing incorrect strategic pivots. The Halo Effect is driven by basic psychology, Rosenzweig points out that “social psychologist Eliot Aronson observed that people are not rational beings so much as rationalizing beings. We want explanations. “

The Halo Effect is attributing a company’s success or failure to its leader or a specific strategy or tactic. People may look at a successful company and believe its acquisition or HR strategy is responsible for the success. This belief then becomes common and other companies replicate the strategy but experience different results. The problem is that the success was probably due to many or alternative factors and just copying one, which may or may not have contributed to the success, does not create the same recipe for success. You may actually be copying part of the strategy or leadership that does not work.

It is the same with individuals. If a company is successful, people are quick to credit the CEO. Articles and books are written about the leader but in reality the company was probably successful because of many factors, both external and internal. Not only then are those who copy the behavior of the CEO disappointed with their results, the successful CEO himself may find failure one year later even if they have not changed.

I have seen this issue many times in sports, both in business and other areas. A manager or coach can be brilliant one year and stupid the next. Yet the manager is the same person, with the same philosophy and strategy. Either the previous success was misattributed or the failure is. I remember when Claudio Renieri shocked everyone as Manager of Leicester City when they won the Premier League in 2016, only to be fired the club in 2017.

The reality is that the success is a combination of factors (including luck) and his strategy was not singly responsible for success or failure. This argument is not simply academic, as it impacts who the club hires and releases. Extended to the business world, it impacts who you put in leadership positions, promote or remove.

There are many factors that contribute to the Halo Effect. Most managers do not usually care to review discussions about data validity and methodology and statistical models and probabilities. They prefer explanations that are definitive and offer clear implications for action. They want to explain successes quickly, simply, and with an appealing logic.

There are multiple reasons that the Halo Effect is so widespread. First, it is impossible to experiment or test real life scenarios to determine actual cause and effect. Second, people love a story and the Halo Effect creates a nice (albeit inaccurate) success story. Third, many, including data analysts, mistakenly equate correlation with causality. Fourth, people often neglect to look at the overall ecosystem and try to simplify a situation to a vacuum. They look for one answer when the reality is much more complex. Finally, people often neglect to account fully for the impact of competition.

You can’t experiment to determine business success

When looking for why a company succeeds, you cannot replicate the methodology an app or game developer would use on why a feature works. There is no way to bring the rigor of experimentation to questions like why a company tripled in revenue or experienced a sales decline. If you want to know the best way to manage an acquisition, you cannot buy 100 companies, manage half of them in one way and half in another way, and compare the results. Without the ability to run a statistically significant experiment, people search for other ways to understand success and failure.

Reinforcing this problem is the confirmation bias, since there is not objective data people pull the data that confirms what they believe is the cause. People do not recognize good leadership unless they have signs about company performance from other things that can be assessed more clearly—namely, financial performance. Roswenszweig writes, “and once they have evidence that a company is performing well, they confidently make attributions about a company’s leadership, as well as its culture, its customer focus, and the quality of its people….But when some researchers took a closer look, they found that …the scores … for a given company turn out to be highly correlated—much more than should be the case given variance within each category. Furthermore, many of the scores were very much driven by the company’s financial performance, just what we would expect given the salient and tangible nature of financial results. “ In effect, they back into confirming their original hypothesis on the cause of a success (or failure).

Pick any group of highly successful companies and look backward, relying either on self-reporting or on articles in the business press, and you will find that they are said to have strong cultures, solid values, and a commitment to excellence. This does not prove these cultures are actually strong, but they are viewed as strong due to the company’s success.

People love stories

Marketers have known for a long time, as have entertainment companies, the power of stories. Rather than explaining the features in a pair of runners that would help in a soccer match, a good marketer will explain how the shoes are developed in conjunction with world-class athletes, who then go to the factory to test them. This type of story is much more compelling (even if false) than an objective review of facts. The same problem contributes to the Halo Effect.

People love to hear how the charismatic leader led the company from a start up to a Unicorn. These stories sell books and magazines (or generate web traffic). The tendency to attribute company success to a specific individual is hard to resist. We love stories because they do not simply report disconnected facts but make connections about cause and effect, often giving credit or blame to individuals. As Rosenzweig writes, “our most compelling stories often place people at the center of events. When times are good, we lavish praise and create heroes. When things go bad, we lay blame and create villains. Facts were assembled and shaped to tell the story of the moment, whether it was about great performance or collapsing performance or about rebirth and recovery. “

The book uses the examples of Cisco and ABB to reinforce the point about the power of stories. Both companies were written about in glowing terms, with many trying to replicate the approaches of John Chambers at Cisco and Percy Barnevik at ABB. As long as Cisco was growing and profitable and setting records for its share price, managers and journalists and professors inferred that it had a wonderful ability to listen to its customers, a cohesive corporate culture, and a brilliant strategy. And when the bubble burst, observers were quick to make the opposite attribution. The same happened with ABB, where Barnevik went from revered business leader to scandal plagued miscreant. The reality was neither Chambers nor Barnevik changed, the story changed to fit the new performance.

Equating correlation with causality

One of the most dangerous manifestations of the Halo Effect is equating correlation with causality. While the correlation may be useful for the purposes of suggesting causal hypotheses, it is not a method of scientific proof. A correlation, by itself, explains nothing. Rosenzweig writes, “by looking only at companies that perform well, we can never hope to show what makes them different from companies that perform less well. I call this the Delusion of Connecting the Winning Dots, because if all we compare are successful companies, we can connect the dots any way we want but will never get an accurate picture. “

Companies that consider themselves data driven and even business intelligence teams, often fall into this correlation trap. They start with a success (or failure), either their own or another company, and then dissect it by looking for correlations between the success and a certain activity. Eventually you will find something, even if the correlation is coincidental. If you are starting with a hypothesis, I guarantee you there will be one relationship that “proves” your hypothesis, no matter what you are claiming (and how accurate you are). A good data scientist can even prove a statistica significance to almost anything, they will find some test that “proves” their claim.

I always laugh at the articles written around the World Cup or Super Bowl about how the region or league of the winner will impact an election or economic growth (i.e. if a California team wins the Republicans will win the next election). Obviously, it is just random luck but there is so much activity occurring at any time there will be some correlational relationship. The sporting event, though, is not driving the activity (there is no causality) and is no more likely to predict an up economy as a coin flip would.

People fall into this trap because they are looking for an easy answer. Rather than understanding all the factors that contribute to a drop in registrations in a region, the analytics team will point to a new product introduction that occurred roughly the same time. For them, it is problem solved. Only when their sales continue to fall or extends to other regions do others begin to see that the problem is much more complex.

Single explanations often do not exist

Another issue driving the Halo Effect is that most results are not driven by one factor. So many things contribute to company performance that it is impossible hard to know exactly how much is due to one particular factor. Even if we try to control for many things outside the company we cannot control for all the many different things that go on inside the company.

All of us can probably think of examples that show this phenomenon. In my case, I was once asked during an exit interview why I quit. Rather than one answer, which the interviewer was expecting, it was a series of experiences over a year. There were several triggers but you could not attribute it to any one variable, as much as the HR person was hoping. Another example is when one of our products out-performed projections. While it would have been easy to explain it as one brilliant decision, and that is what the CEO was looking for, it was a combination of product changes, changes with the competition and a platform shift.

Rosenzweig writes, “the new CEO does something—such as setting new objectives, or bringing about a better market focus, which may help improve the corporate culture, or overhauling the approach to managing human resources, and so on. The improved performance we attribute to the CEO almost certainly overlaps with one or more other explanations for company success. Which brings us to the nub of the problem: Every one of these studies looks at a single explanation for firm performance and leaves the others aside. That would be okay if there were no correlation among them, but common sense tells us that many of these factors are likely to be found in the same company.”

The competitive impact

Related to the impact of multiple variables on performance is the competitive environment. I can be a great leader but if Jeff Bezos and Satya Nadella lead my competitors, my company would probably not perform very well and my leadership would be used as an example of what not to do. Now say I am exactly equally competent but I run an airline. My competitors are not exactly rock stars and we probably out-perform them. Then books and articles get written about how strong my leadership is and what aspects should be copied. In either case, I am doing the same thing but the Halo Effect attributes much of the result to my leadership. Same can be said for HR policies (open office, free lunch, etc) and any other driver of success. If looked at in a vacuum, the Halo Effect creates very misleading results.

As Rosenzweig writes, “the Delusion of Absolute Performance diverts our attention from the fact that success and failure always take place in a competitive environment. It may be comforting to believe that our success is entirely up to us, but as the example of Kmart demonstrated, a company can improve in absolute terms and still fall further behind in relative terms. Success in business means doing things better than rivals, not just doing things well.”

Success is short-lived, especially now

The final point that Rosenzweig makes is that success is short lived. He points out that only 74 companies on the S&P 500 in 1957 were still on the S&P 500 in 1997, forty years later. Of the 74, only 12 outperformed the overall S&P 500 index (they survived but did not thrive). Thus, what makes a company great today probably will not make it great tomorrow, but more realistically it probably is not one thing and as it evolves so will the company.

Next steps

The Halo Effect is a result of our attempts to over-simplify the world. Success and failure are driven by multiple factors and there are no shortcuts to achieving great results. While we can learn from others, we need to remain diligent and make sure not to draw simplistic conclusions. At the end of the day, there is no easy answer and no silver bullet to generate success, it comes from repeatedly make smart, data driven decisions consistent with a coherent strategy.

Key takeaways

- The Halo Effect is attributing success or failure to an individual or specific action, which is often misleading.

- The Halo Effect is caused by an inability to do experiments in the real world on the success of a business, people loving stories, mistakenly equating correlation with causality, looking for a single answer to a complex problem and neglected the impact of competition.

- There is not one simple answer on how to succeed or how to avoid failure, but you must make a series of good decisions based on data.