Last year, I had the opportunity to attend (virtually) the The Peter Drucker Institute’s Forum on Leadership. What I found particularly compelling (and why I attended) was that the majority of the speakers were successful business leaders, rather than people whose primary calling was providing advice. I always prefer proven actions to theories.

Below, I am highlighting some of the key highlights and takeaways for companies in the gaming space, particularly tied to innovation, leadership, remote work and leading during a crisis.

The kryptonite of innovation: Excel

One of the most interesting lessons from the seminar was a story from Scott Cook, founder and CEO of Intuit, recalling one of Clayton Christensen’s (the guru of innovation) experience with innovation at Intel. According to Cook, Christensen identified spreadsheets as the root cause of Intel’s inability to innovate. He had been brought in by Andy Grove to help Intel and was given access to all new businesses that Intel had created. At the time, Intel had launched 60 new business initiatives, and every single one failed.

As Intel was a huge company, there was robust documentation for all the initiatives. Christensen reviewed the documents and found that the common flaw was the spreadsheet. Whatever the company’s required IRR (internal rate of return) in the proposal, the P&L always showed you would get that IRR. Yet, in the end, all 60 had failed. The spreadsheets actually focused the teams on manipulating the numbers rather than finding product/market fit. This lesson resonated strongly with me, as I have seen many companies in the gaming space try to use robust analysis to greenlight new game projects and the reality never came close to the spreadsheet (in fact, the performance of the projects seemed uncorrelated to the projections).

Key takeaway: Using spreadsheets to analyze a new business venture is worthless or even creates negative value. It is impossible to predict accurately the new ventures performance and takes away from testing businesses in the wild.

The opposite of spreadsheets, tools to generate innovation

While spreadsheets are not the solution to innovating, several speakers provided excellent guidance. One speaker provided a clear alternative to Intel’s failed strategy of innovating by financial analysis. Rather than try to pick winners, admit you do not know what projects will succeed. In stark contrast to Intel, Bosch invested in 200 projects in two years. It gave each a small amount of seed investment. After three months, the teams had to prove the project had traction, using predetermined KPIs. After three more months, the team again had to prove it had promise; at this stage Bosch kills 70 percent of projects, with the others receiving additional investment. After another three months, it kills another seventy percent of projects, adding to the investment in the survivors.

Howard Yu, the LEGO professor of Innovation at IMD Business School explained that companies have no trouble trying disruptive innovation but scaling it. This problem is one I experienced in multiple large companies that were trying to expand into new areas.

These projects turn into side hobbies and never impact the core business, moreover, they leave the company vulnerable to disruption. I once joked that an effort I led at a big company had the promise of being a footnote on its financial statements after five years if we continuously outperformed our plan.

Even when buying companies for innovation, companies often fail to scale this disruption. To overcome this situation, the leadership team must have a shared vision of the future. They and their Board needs to have difficult conversations, including firing and hiring. Most importantly, the CEO has to have a curious mind and recognize what kind of world we live in to capitalize on opportunities and mitigate the biggest risks. A great example of a “curious” executive is Bill Gates, who reads over 50 books a year.

Key takeaways: The best way to grow innovation is testing multiple initiatives, evaluating them critically, stopping the majority of projects and then increasing investment in those showing traction. For a company to innovate and not simply play at innovation, it also needs a curious leader who builds a shared vision of the future.

The value of micro-businesses

Another great insight came from Kevin Nolan, the CEO of GE Appliances. GE Appliances is the fastest growing appliance business in North America and owned by Haier, the Chinese conglomerate known for innovation. Nolan discussed his experience at GE Appliances, where the company was originally built on efficiency and productivity but had been dying slowly due to slow moving ideas and bureaucracy. In the fast evolving consumer appliance environment, GE needed to be creative and nimble but instead had become bureaucratic. Ideas were based on the weight of PowerPoint presentations rather than product/market fit. Success was measured on getting into next year’s budget. GE was slow moving and not responsive to the market, unable to compete in a fast paced, short cycle business. Thus, GE sold the unit to Haier, though Nolan expected more of the same from the new Chinese owners.

Instead, Haier realized that employees want to be entrepreneurs. It broke the business into small pieces so it could focus on agility and competition. Haier preached that the only person employees should listen to is the users, they pay the salary, not the company. The philosophy being that your boss is not inside your company but outside, your consumer. Nolan said, “burn your org charts, they represent hierarchy, bureaucracy.”

It broke company down from 4 to 14 product lines and shifted to micro-enterprises. By micro-enterprises, business lines or products that had full P&L responsibility and autonomy. Effectively, GE created a collection of CEOs. The idea behind the micro-businesses is that the team needs to live in a zero distance world from its customer. Every micro-enterprise looks at their individual customers, not the aggregate customers of the company.

The goal for Nolan and Haier was to get zero distance between the customer and employees, perpetually getting the gap smaller and smaller. It was also critical for every micro-business to get tight with its commercial team. That is where got actionable feedback, not one of the staff functions. As Nolan said, “finance can’t tell you what you need to do in the future.”

With this strategy of micro-businesses, GE Appliances is now the fastest growing company in the very competitive North American market and the number one smart home company. It also has the highest employee satisfaction rating in the industry.

Key takeaways: In the gaming space, you can set up every product as a micro-business, with P&L responsibility. Give the team autonomy and allow them to focus on the specific customers of their game, rather than the entire company.

Inverted pyramid of leadership

Any strong management conference will include interesting ideas about leadership, and this one did not fail to deliver in that area. One of the speakers, John Ferriola, the former CEO of Nucor (a company with over 26,000 employees), explained the concept of the inverted pyramid. According to Ferriola, command and control only works where safety and compliance are critical. Otherwise, a business in the 21st century need to invert the pyramid, based on meritocracy and freedom for the employees.

At Nucor, the CEO (at the time, Ferriola) works for the employees, not the other way around. Nucor believes every leader at every level must lead with a servant’s heart; their job is to take care of their team. The leader’s job is to create an environment where others can succeed and then trust that once they create that environment, the team will do the best thing. No leader can have all the knowledge to make always the right decision, instead leverage the cumulative resources of your team to take the best path of action.

As part of the inverted pyramid, every employee can bring ideas or complaints to the CEO, with the caveat that they need to discuss the idea first with their immediate supervision. Then employee can speak directly to the CEO without any fear of reprisal. All employees had the CEO’s office number, home number and cell phone.

Key takeaways: Rather than building a strict hierarchy, structure your company so the leaders can serve their teams and create an environment where employees are empowered to take the best action.

Empowering the top of your pyramid

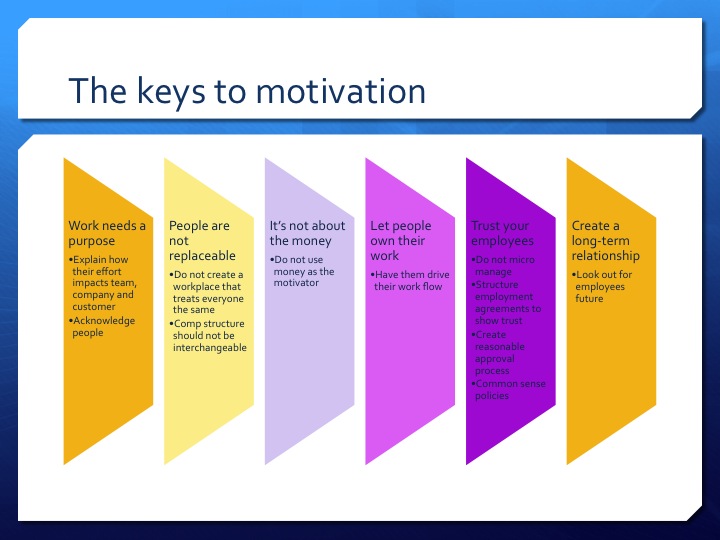

Once you accept the concept of the inverted pyramid, there are many techniques to empower your employees, who are now at the top of the pyramid. Tracey Davidson, the Deputy CEO of Handelsbanken explains it comes down to fundamentally trusting your colleagues. To achieve this trust, you need to align around a common set of core values; at Handelsbanken they have had the same goal and core values for 50 years. For these goals to be successful, they must be:

- Simple

- Easy to remember

- Shared focus

- Focused on satisfying customers, not costs or profit

Ms. Davidson explained that when people have a clear mandate, they do their best work. At a structural level, trusting employees allowed them to decentralize their organization and treat each branch treated as a mini-business supported by the central business (consistent to the conversation about micro-businesses above).

It was interesting how empowering employees converged with creating micro-businesses. In Handelsbanken’s case, by turning each branch into a micro-business, they did not have to change policies or decisions for people to make decisions in new parts of the bank. Each branch controls its own P&L. The branch decides where it is going to spend, where expenditures are pitched on a peer basis. Branches see that if they control costs well, then every new customer has a bigger impact.

Handelsbanken also gives each branch details on costs so they can set their own pricing. The central branch provides all the costs of capital as well as other costs and the local branch then decides pricing and whether or not to loan to a local customer.

As part of empowering the branches, they have to live with consequences of their decisions. If capital exposure cost goes up with a bad customer, it impacts the branch. Branch performance reflects customer performance, not kicked into a group KPI. This philosophy has helped Handelsbanken consistently outperform its peers.

Another example of empowering your team is from the CEO of Michelin, Florentino Menegaux. Menegaux points out that as the leader you need to suck the stress from the organization and your team and return the energy. Michelin started as a command and control culture but he realized it was contradictory to trying to focus on customers. He needed to realign processes to tap into the collective intelligence and understanding of customer, rather than relying on processes. To make this change, and put employees at the top of the pyramid, he identified three keys:

- Trust. Empowerment and performance begins with trust. Never underestimate the casual genius of every human being.

- Freedom. If you want people to think outside of the box, you need to give employees ability to do so.

- Culture. If you want to transform people on the front lines to be empowered, you have to transform the culture and work with everyone to address challenging behaviors.

Menegaux concluded by pointing out that humans collectively are more powerful than a computer but computers allow people to be more human. He suggested we use technology to unleash human potential, rather than measuring 1,000 KPIs.

Key takeaways: To empower your team and move to an inverted pyramid, you need to provide clear and simple goals and allow your employees to figure out the best way to achieve them.

How to lead in a remote environment

The conference explored another element of leadership, particularly important now, leading in a remote or work from home environment. What made someone a great leader even two years ago may not work now, where you can no longer meet informally with your team or easily observe their day-to-day activities.

Donna Flynn, the VP of Global Talent at Steelcase focused on the emphatic traits leaders now need to develop. She identified three keys to leading successfully in a remote environment:

- Be intentional and clear with your team.

- Develop a “third eye” for emotional intelligence, as you need to view your team through an emotional lens.

- Help your team manage both their energy collectively and individually. Well-being is a top line issue for leaders to always consider.

Flynn also provided some useful, more tactical advice:

- Large group discussions are not as interactive, so it is good to follow them up or even precede them with small group discussions.

- You need to connect with your team, not only your direct reports, one-to-one. Focus on frequent touch points across your team and show vulnerability so they open up to you.

- Work from home will be a node in the ecosystem and the office another node. Some will chose to go to the office daily. Others will chose to go for specific activities. Design your processes and team for this cadence of interactions and build the conditions to achieve desired outcomes.

Guy Ben-Ishai of Google added additional insights into effectively leading in a work-from-home or remote environment. According to Ben-Ishai, successful remote leadership comes down to maintaining your presence. If you are not present, you cannot really lead. You can achieve this presence with frequent interactions with a broad number of people, even when working remotely. You should insist on taking the time and having periodic check-ins with employees, colleagues and other leaders.

Key takeaways: In a work-from-home or remote work environment, great leaders need to maintain their presence. You can do this with frequent, personal interactions with teammates, employees and other colleagues.

Using a crisis to improve

Covid has not only provided a challenge in leading remote workers but it also has presented opportunities for many companies. Great leaders can turn a crisis into an opportunity. To lead effectively through a crisis, you need to think outside the box and focus on your customers.

Sara Mathew the Chair of the Board at Freddie Mac recounted the story of one of her greatest professional successes. She joined Dun & Bradstreet as CFO a week before 9/11, which almost put the company out of business. To deal with the crisis, Ms. Mathew brought in the consulting group McKinsey, who proposed a very draconian process to survive. She was tasked with changing Europe to break even. Customers had lost trust in the brand because of data quality. The team was worn out with the issue, it was all they heard day in and day out. Yet there was still a sense of optimism as employees maintained pride in D&B.

Ms. Mathews tried something revolutionary, collaborating with their top competitor. Her goal was to give access to their technology platform and data and convert it into franchise model. In 18 months, she created franchises around the world for every market except three where they were already number one. Europe moved from a loss to a $100 million profit. Customer satisfaction improved 30 points. D&B’s stock price went from $20 to $80 and Ms. Mathews became CEO.

Ms. Mathews explained that this success, driven by a crisis, was not genius but the result of trying a radical idea. She also highlighted that the idea did not come from the top, it came from a customer.

In addition to the example of Ms. Mathew, Jorgen Vig Knudstorp, LEGO’s Executive Chairman explained how LEGO used the crisis as an opportunity to reinforce its mission. LEGO annually spends about $300 million to promote children with challenges to learn through play. LEGO increased its investment another $100 million during the pandemic for similar initiatives, as the non-profits they work with were facing extraordinary challenges to continue their work. Knudstorp explains that when you are under pressure, it is a good opportunity to put your money where you mouth is.

Key takeaways: To navigate your way out of a crisis, listen to your customers to come up with novel solutions.

Key takeaways:

- The best way to grow innovation is testing multiple initiatives, evaluating them critically, killing the majority and then increasing investment in those showing traction in a regular cycle. For a company to innovate and not simply play at innovation, it also needs a curious leader who builds a shared vision of the future.

- Rather than building a strict hierarchy, structure your company so the leaders can serve their teams and create an environment where employees are empowered to take the best action.

- To navigate your way out of a crisis, listen to your customers to come up with novel solutions.