Happy holidays to everyone and I hope you all have a wonderful New Year! Please come back for new posts in 2018, I am looking forward to writing about some interesting topics. Have a great holiday season!

Happy holidays to everyone and I hope you all have a wonderful New Year! Please come back for new posts in 2018, I am looking forward to writing about some interesting topics. Have a great holiday season!

When reading Michael Lewis great book about Daniel Kahneman and Alex Tversky, The Undoing Project, Lewis references several times the Yom Kippur War. The war had a big influence on the thinking of Kahneman and Tversky.

The references particularly piqued my interest because I was too young to understand what was happening during the conflict but it did not make its way into most history texts when I was in school. It was also interesting because in a matter of days it went from a war that looked like it could destroy Israel, there were rumors they were even considering the nuclear option, to a war where the entire Egyptian Third Army was encircled.

With changes on the battlefield that dramatic there had to be fantastic lessons in decision making so I decided to learn more about the conflict. By reading The The Yom Kippur War: The Epic Encounter That Transformed the Middle East by Abraham Rabinovich, I learned how the Yom Kippur War is a great case study in the biases and paradigms that form the foundation of Kahneman’s Thinking, Fast and Slow.

The Yom Kippur War highlighted one of the biggest errors in decision-making, over-confidence. If Israel had not mobilized its reserves shortly before the war started, the odds at the beginning of war would be in the Arabs’ favor by several orders of magnitude. The 100,000 Egyptian soldiers and 1,350 tanks west of the Suez canal faced 450 Israeli soldiers in makeshift forts and 91 Israeli tanks in the canal zone. On the northern front, where Israel faced Syria, the Syrians enjoyed 8 to 1 superiority in tanks and far greater in infantry and artillery.

The limited forces Israel deployed on both the Syrian and Egyptian fronts opposite vastly larger enemy armies reflected a self-assurance induced by the country’s stunning victory in the Six Day War. Israel believed it had attained a military superiority that no Arab nation or combination of nations could challenge.

Even when war appeared likely, the Israelis moved only a small number of forces to face the Syrians. Abramovich quoted the Israeli Chief of Staff, Dado Elazar as saying “’We’ll have one hundred tanks against their eight hundred, that ought to be enough.’ In that sentence, Elazar summed up official Israel’s attitude towards the Arab military threat.“

This overconfidence almost led to the collapse of the Israeli military. Abramovich wrote, “a common factor behind all these failings was the contempt for Arab arms born of that earlier war, a contempt that spawned indolent thinking.“

The reality was that the Egyptian and Syrian forces were not like their predecessors in earlier conflicts, but instead had the most modern Soviet weapons and a more disciplined and professional military. The overconfidence that prompted the Israeli military to not take seriously its opponents put its soldiers in an untenable position that led them initially to be overwhelmed.

Given that you probably do not lead an organization with tanks and artillery, you may ask why should I care whether the Israeli military was overconfident. The lesson, however, that is pertinent is that underestimating your competition could be disastrous. Just because your competitor has not been able to develop a product in the past that is of comparable quality to your product, does not mean that they will never have that capability. You may dominate the market but your competition is working on ways to jump over you.

You also may underestimate their likelihood to want to compete in certain market sectors. You may have gained 80 percent of the racing game market after pushing your top competitors away so you move your development to sports games because you now own racing games. Do not assume they do not have a secret project to create a new racing game that will suddenly make your product obsolete.

The Yom Kippur War highlighted one of the biases that Kahneman and Tversky have regularly wrote about, confirmation bias. Confirmation bias is when you ignore information that conflicts with what you believe and only select the information that confirms your beliefs.

In the Yom Kippur War, Egypt and Syria were able to almost overwhelm the Israelis because the Israelis did not expect to be attacked by overwhelming force. Although the Arab states did launch a surprise attack, it should not have been a surprise. Both Egypt and Syria mobilized huge numbers of forces (which was visible to the Israelis), while multiple intelligence sources and even the leader of Jordan warned the Israelis an attack was imminent. It was confirmation bias, however, that kept the Israelis from believing they would be attacked and preparing for it (until the last minute).

First, the Israelis ignored any information that did not support their theory that they would not be attacked. Abramovich writes, “Eleven warnings of war were received by Israel during September from well-placed sources. But [Head of Military Intelligence] Zeira continued to insist that war was not an Arab option. Not even [Jordan’s King] Hussein’s desperate warning succeeded in stirring doubts.”

Explaining away every piece of information that conflicted with their thesis, they embraced any wisp that seemed to confirm it. The Egyptians claimed they were just conducting exercises while the Syrian maneuvers were discounted as defensive measures. Fed by this double illusion—an Egyptian exercise in the south and Syrian nervousness in the north—Israel looked on unperturbed as its two enemies prepared their armies for war in full view. Abramovich writes, “the deception succeeded beyond even Egypt’s expectations because it triggered within Israel’s intelligence arm and senior command a monumental capacity for self-deception. ‘We simply didn’t feel them capable [of war].’”

As I mentioned above, examples of decision making flaws were abundant on both sides and Egypt also suffered greatly because of confirmation bias. When Israel began its counter-attack that eventually led to the encirclement of the 3rd Army, the Egyptians President Sadat only looked at data that supported his hypothesis. Given the blow the Israelis had received at the start of the war and the fact that they were heavily engaged on the Syrian front, the Egyptians were thinking in terms of a raid, not a major canal crossing. An early acknowledgement of the Israeli activity could have stemmed the attack and possibly left the Egyptians in the superior position but they only saw what they wanted to see.

I come across confirmation bias almost weekly in the business world. One example you often see in the game space is when a product team is looking to explain either a boost in performance or a setback. If the numbers look good, they will often focus on internal factors, such as a new feature, and “confirm” that this development has driven KPIs. If metrics deteriorate, they will often focus on external factors, maybe more Brazilian players, that confirm the problem is outside of their control. These examples of confirmation bias often lead to long delays identifying and dealing with problems or shifting too many resources to reinforce features that do not have an impact.

Another major decision making flaw that the Yom Kippur War highlights is avoiding reality. One of the leading Israeli commanders did not venture out of his bunker and relied on his own pre-conceptions of what was going on rather than the actual situation. Rabinovich writes that “although he was only a short helicopter trip from the front, [General] Gonen remained in his command bunker at Umm Hashiba, oblivious to the true situation in the field and the perceptions of his field commanders. As an Israeli analyst would put it, Gonen was commanding from a bunker, rather than from the saddle.”

On the Egyptian side, to avoid panic, the Egyptian command had refrained from issuing an alert about the Israeli incursion. Thus, the Israeli forces were able to pounce on unsuspecting convoys and bases. There had been a number of clashes involving Israeli tanks and the paratroopers but no one in Cairo—or Second Army headquarters—was fitting the pieces together.

Thus, rather than successfully defending against the Israelis, the Egyptians left their troops blind to what was happening.

If your game or product is not performing, you need to understand what is really happening. I have often seen products soft launched in tier three markets that show poor KPIs. Rather than reporting these KPIs to leadership, they will proceed with the real launch in tier one markets. This pre-empts the product team from fixing the product and also wastes money with a failed launch.

Another decision-making bias demonstrated in the Yom Kippur war was assuming the past would repeat. As I wrote earlier, the Israelis would assume the Arabs would fight poorly because they did in previous wars, including the Six-Day War in 1967, where Israel routed the Arab States. They thus did not prepare their forces for any different type of opponent or different weaponry.

This bias also contributed to their failure to realize they would be attacked imminently. When General Shalev, assistant to Israel’s Commander in Chief, was warned of a likely attack, he reminded the so-called alarmist that he had said the same thing during a previous alert in the spring, “you’re wrong this time too,” he said. Because a previous alert was wrong, the Israeli high command discounted a clear danger.

In the game space, you frequently see decisions made based on looking in the rear view mirror. I have seen many executives decide to make a type of game – first person shooter, invest express sim, tower defense, etc – because these are the hot type of games. Then when their game comes to market and fails, they do not understand why they always seem to be behind the trends.

I have written several times about the work of Kahneman and Tversky, highlighted in the book Thinking, Fast and Slow, and how helpful it is in understanding decision-making and consumer behavior. One of the most enlightening experiments done Kahneman and Tversky, the Invisible Gorilla experiment, shows the difference between tasks that require mental focus and those we can do in the background.

In this experiment, people were asked to watch a video of two teams playing basketball, one with white shirts versus one with black shirts (click to see Invisible Gorilla experiment). The viewers of the film need to count the number of passes made by members of the white team and ignoring the players wearing black.

This task is difficult and absorbing, forcing participants to focus on the task. Halfway through the video, a gorilla appears, crossing the court, thumps its chest and then continues to move across and off the screen.

The gorilla is in view for nine seconds. Fifty percent, half, of the people viewing the video do not notice anything unusual when asked later (that is, they do not notice the gorilla). It is the counting task, and especially the instruction to ignore the black team, that causes the blindness.

While entertaining, there are several important insights from this experiment

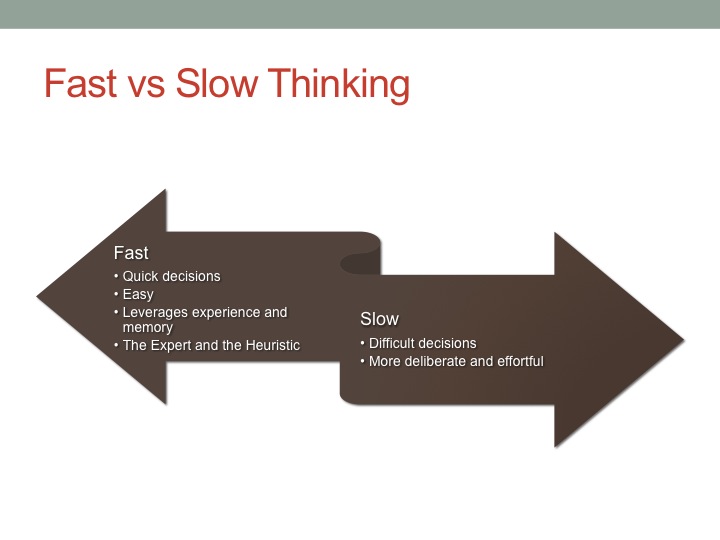

The Invisible Gorilla also serves as a framework to understand the two systems people use to think. System 1 operates automatically and quickly, with liitle or no effort and no sense of voluntary control. An example of System 1 thinking would be taking a shower (for an adult), where you do not even think about what you are doing.

System 2 thinking is deliberate, effortful and orderly, slow thinking. System 2 allocates attention to the effortful mental activities that demand I, including complex computations. The operations of System 2 are often associated with subjective experience of agency, choice, and concentration. The highly diverse operations of System 2 have one feature in common: they require attention and are disrupted when attention is drawn away .

The automatic operation of System 1 generates surprisingly complex patterns of ideas, but only the slower System 2 can construct thoughts in an orderly series of steps.

Understanding System 1 and System 2 has several implications. First, if you are involved in an activity requiring System 2 thought, do not try to do a second activity requiring System 2 thought. While walking and chewing bubble gum are both System 1 for most people and can be done simultaneously, negotiating a big deal while typing an email are both System 2 and should not be done at the same time.

Second, do not create products that require multiple System 2 actions concurrently. While System 2 is great for getting a player immersed in a game, asking them to do two concurrently will create a poor experience. A third implication is when onboarding someone to your product, only expose them to one System 2 activity at a time.

I like to use examples from the game space to illustrate how understanding Kahneman and Tversky’s work can impact your business. In this example, Urbano runs product design for a fast growing app company at the intersection of digital and television. He has built a great sports product that allows players to play a very fun game while watching any sporting activity on television. Unfortunately, Urbano’s company is running out of funds and the next release needs to be a hit or else they will not survive. Although the product has tested well, Urbano is nervous because of the financial situation and decides to add more to the product, to make the app based on what happens the past three minutes during the televised match. They launch the app and although players initially start playing, they never come back and the product fails.

Another company buys the rights to the product and conducts a focus test. They find out users forgot what happened on television because they were focusing on the app and then could not complete the game. They take out the part requiring attention to the televised match and the product is a huge success. The difference was that the latter did not require multiple System 2 thinking simultaneously, it left television watching as a System 1 activity.

I recently finished a course on EdX, Digital Branding and Engagement from Australia’s Curtin University, and while it had a lot of information that is commonly known, there were also some tidbits I wanted to share.

The focus of marketing is now on an engagement model and not a sales model, where you provide actual value to your customer or player. Traditional disruptive one-way advertising messages are being replaced with deeper two-way relationships with consumers. As a business, you have to consistently engage your customers; which requires compelling content that is interesting, creates value, and has opportunities for interaction. A true value exchange is one that creates loyal customers.

A key dynamic driving this engagement model is that consumers are no longer captive. A captive audience is one where a message is created and channeled to consumers who passively receive content. Consumers are now the beneficiaries of a power shift. The power shift is from media companies who used to control what consumers saw, when they saw it, and how they saw it. Now the power shift is with the consumers.

As they pointed out in the course, the notion of captive audiences is one that lives in the past, even in the online environment. There is a growing acknowledgement that marketing has changed more in the past one to two years, than it has in more than half a century before.

To succeed in this environment you need both to communicate interactively and add value. Give them something for interacting. It could be tips, discounts, compelling stories, etc., with the key being it needs to be something they value.

Consumers now expect two way communication. When they are dissatisfied, not only will they communicate this to you but they expect a (fast) response. Consumers expect a two-way dialogue with brands and personalized ads relevant to their needs. Even if you are sending a newsletter, it should be personalized based on your customers’ preferences.

An evolving opportunity with social media marketing is participation marketing. With participation marketing, you build a team around an event that is going to happen on social media, then have them talk about it and respond very quickly (Super Bowl, Oscars, World Cup, eSports, etc.). Rather than creating the event, you piggyback on to a topic people are engaged with, connect your product or game with that content, and create a conversation with potential customers.

Once you engage with customers, on their terms, you can then bring them to your assets. Reaching people in areas they are most interested in, engaging them with content that is directly relevant and taking them through to your owned resources.

Unlike the Mad Men era, content is no longer about making the brand look great. Good content is now focused on the customer and not the brand. The key is when creating content you should put people first, with the product in the background. Good content should be focused on the customer, not the brand.

At a high level, there are four keys to creating compelling marketing content:

Overall, a successful content strategy is clear and aligned internally not only in the marketing department but with all decision makers.

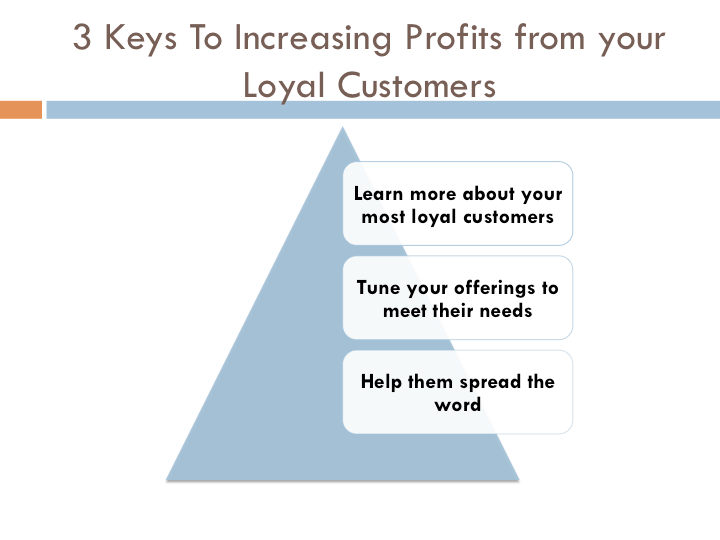

While the key to business success is creating happy and loyal customers, you still need to get them to generate more revenue. A good NPS score and low churn rate shows your customers are satisfied but you only benefit when these customers act on their positive feelings. An article in Harvard Business Review, Make it Easier for Customers to Buy More by Bain Capital’s Rob Markey, shows how to convert this satisfaction into profits.

The first key to generate more profits from your loyal customers is to understand them better. Markey makes the point that companies focus on learning why detractors, or unhappy customers, are dissatisfied but they do not put the same effort in understanding why the happy customers are happy. As Markey writes, “Converting feelings into action requires knowing exactly what you did to earn their loyalty, so you can replicate the action and extend it. To maintain that kind of intimate relationship with your most loyal customers, you have to create effective mechanisms for staying in close touch.”

Add to all of your communication channels feedback loops to ascertain why they love your company. Have your account or customer service reps ask customers why they first became enthusiastic. When sending out NPS surveys, make sure you ask those providing high scores the reason they gave such a score. Have customers post stories on social media on why they like your offering. Have events for your top customers and ensure part of the agenda is having customers discuss how they fell in love with your brand. Use all of your channels not only to help your customers but to learn from them.

When communicating with your best customers, you will learn both what they like and do not like about your offering. You will also understand if your competitors are offering something they want that you do not offer. Markey writes, “ideally, your offerings should be so attractive to your loyalists that they have no reason to look elsewhere for additional products or services.”

Once you understand your customers needs, then adjust your product to meet these needs. It may be by providing additional features or more support services. It could also entail offering your product through new distribution channels or in another format. The key is understanding what your best customers want from your product but are not getting, then adjusting your product to fill this need so they do not move to competitors.

Since your most loyal customers by definition love your offering, you want to harness this positive vibe by getting them to promote you to their friends. As people communicate best via stories, you need to provide them with stories that they can share. These stories can range from great interaction with your staff (maybe customer service, VIP management or on Facebook), a great experience with your game or product or even a little bonus you got via email. Once they have the stories, you need to facilitate them sharing the stories. This sharing often is by social media but it can be video testimonials on your website or even quotes in your game.

While it is critical to create incredibly satisfied customers, that is not the end of the battle. You need to learn from them, use this knowledge to make your products even more suited to them and then turn them into advocates.

As promised last month, I will spend a few blog posts summarizing Thinking, Fast and Slow by Daniel Kahneman. Before diving into the heuristics, biases and processes that he and his colleague Amos Tversky identified, it is important to understand why he wrote the book and why it is so useful. Fortunately, he largely does this in his introduction so it is a great place to start.

First, Kahneman points out that the goal of his research is not to prove we are idiots but to help us minimize bad decisions. Understanding flaws in human decision-making is no more insulting or denigrating than writing about diseases in a medical journal belittles good health. Rather, our decision-making is generally quite good, most of our judgments are appropriate most of the time, but there are systemic biases that if we understand can make our decision-making more effective.

By understanding Kahneman’s work, you will be better able to identify and understand errors of judgment and choice, in others and then yourself. As Kahneman points out, “an accurate diagnosis may suggest an intervention to limit the damage that bad judgments and choices often cause.”

At its roots, Kahneman began his career trying to determine if people consistently made biased judgments. Long story short, we do.

One example drove this determination home to Kahneman and Tversky and probably will to you also. Early in their collaboration, both Kahneman and Tversky realized they made the same “silly” prognostications about careers that toddlers would pursue when they became adults. They both knew an argumentative three year old and felt it was likely that he would become a lawyer, the empathetic and mildly intrusive toddler would become a psychotherapist and the nerdy kid would become a professor. They, both smart academics, neglected the baseline data (very few people became psychotherapists, professors or even lawyers compared with other professions) and instead believed the stories in their head about who ended up in what careers was accurate. This realization drove their ensuing research, that we are all biased.

The broad impact of Kahneman and Tversky’s work drives home it’s importance to everyone. When they published their first major paper, it was commonly accepted in academia that:

Not only did these two assumptions drive academia (particularly economics and social sciences) but also their acceptance often drove business and government decisions. The work laid out in Thinking, Fast and Slow, however, disproved these two assumptions and thus drove entirely different decisions to generate strong results.

Scholars in a host of disciplines have found it useful and have leveraged it in other fields, such as medical diagnosis, legal judgment, intelligence analysis, philosophy, finance, statistics and military strategy. Kahneman cites an example from the field of Public Policy. His research showed that people generally assess the relative importance of issues by the ease with which they are retrieved from memory, and this is largely determined by the extent of coverage in the media. This insight now drives everything from election strategy to understanding (and countering) how authoritarian regimes manipulate the populace.

Kahneman and Tversky were also careful to ensure the subject of their experiments were not simply university students. By using scholars and experts as the subject of their experiments, thought leaders gained an unusual opportunity to observe possible flaws in their own thinking. Having seen themselves fail, they became more likely to question the dogmatic assumption, prevalent at the time that the human mind is rational and logical. I found the same myself and am confident that you will also. The idea that our minds are susceptible to systematic errors is now generally accepted.

While Kahneman and Tversky’s early work focused on our biases in judgment, their later work focused on decision-making under uncertainty. They found systemic biases in our decisions that consistently violated the rules of rational choice.

Again, we should not discount our decision-making skills. Many examples of experts who can quickly make critical decisions, from a chess master who can identify the top 20 next moves on a board as he walks by to a fireman knowing what areas to avoid in a burning building, experts often make critical decisions quickly.

What Kahneman and Tversky identified, though, is that while this expertise is often credited with good decision making, it is more of retrieving information from memory. The situation serves as a cue or trigger for the expert to retrieve the appropriate answer.

This insight helps us avoid a problem where our experience (which we consider intuition) does not actually help but hinders. In easy situations, intuition works. In difficult ones, we often answer the wrong questions. We answer the easier question, often without noticing the substitution.

If we fail to come to an intuitive solution, we switch to a more deliberate and effortful form of thinking. This is the slow thinking of the title. Fast thinking is both the expert and heuristic.

Many of my readers are experienced “experts” from the mobile game space, so I will start with a hypothetical example that many of us can relate to. In this example, Allan is the GM of his company’s puzzle game division. He has been in the game industry over twenty years and has seen many successful and failed projects. The CEO, Mark, comes to Allan and says they are about to sign one of three celebrities to build a game around.

Allan knows the demographics of puzzle players intimately and identifies the one celebrity who is most popular with Allan’s target customers. Nine months later they launch the game and it is an abysmal failure. Allan is terminated and wonders what he did wrong.

Allan then looks over his notes from when he read Thinking, Fast and Slow, and realizes his fundamental mistake. When Mark came to him and asked which celebrity to use, Allan took the easy route and analyzed the three celebrity options. He did not tackle the actual question, whether it was beneficial to use a celebrity for a puzzle game and only if that was positive to pick between the three. If he had answered the more difficult question (difficult also because it would have set him against Mark), he would have found that celebrity puzzle games are never successful, regardless of the celebrity. Although it may have created tensions at the time with Mark, he probably would have been given an opportunity to create a game with a higher likelihood of success and still be in his position.

Although I have written about the need to focus and personally always try to, it is much easier said than done. I recently came across a blog post from VC Mark Suster, Why Great Executives Avoid Shiny Objects that does a great job of stressing the importance of focus on the important. One quote by Suster drives home the problem, “many leaders fall into the trap of doing too many things but not accomplishing enough.” Suster makes the point that it is most important to complete the important things, not to start a lot of things.

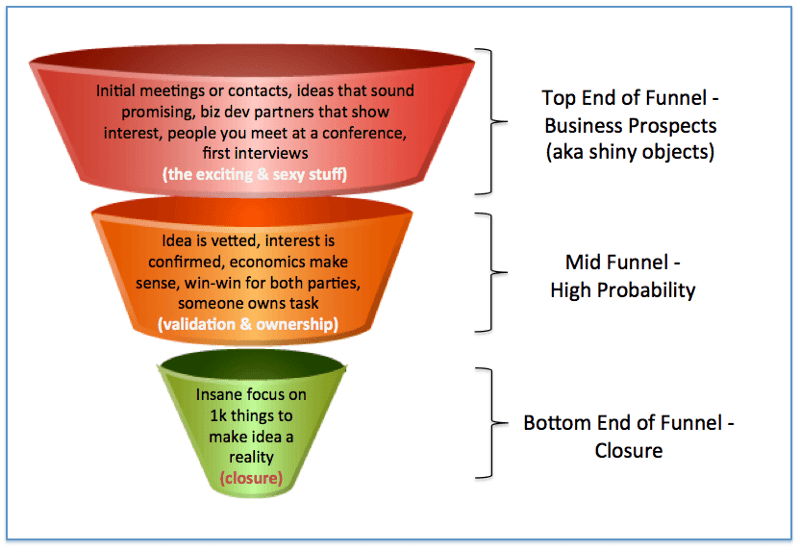

Suster points out that while it is great to talk potential deals with a dozen companies or interview twenty candidate for a position, actual value is driven when you close a deal or have a candidate start at your company. Suster uses the graphic below to differentiate what is important.

The top of the funnel is what he describes as shiny objects. They are activities that make you feel and appear busy, often make great conversation items with your boss or at Board meetings, but in and of themselves do not create value. While you do need a funnel so you can eventually achieve the important thing, you should not spend a disproportionate amount of your time on it. As Suster says, “having interesting and frequent opportunities at the top of your funnel is important, of course, but the ultimate score is only measured on the bottom end of the funnel.”

Executives do not always pursue the top of the funnel because they do not understand the relative value, it is often the path of least resistance. It is relatively easy having a first business meeting and showing your Powerpoint or talking to someone you met at a conference, while analyzing a potential deal and negotiating the final agreement is very hard and time consuming. Sometimes people focus on the top of the funnel because it makes them look busy but is actually the easy route.

To truly succeed, and make sure your people succeed, you need to be “obsessed” with the critical tasks as Suster is. It’s why he “[is] willing to disengage at times from the flurry of ‘activity’ because when [he has] something that needs to be finished the only way [he] know[s] how is maniacally focus on the bottom end of [his] funnel.”

You should build your own funnel, analyze your activities, and make sure you are spending most of your time on the Bottom End of Your Funnel, my guess is you will be amazed at the results.

Anyone reading my blog knows my passion and respect for behavioral economics and consumer behavior, I consider these fields key to successful business. Putting my money where my mouth is, I am now recruiting a consumer behavior product manager to join my free to play team on the Isle of Man. This position will be critical as we continue to grow the free to play (social/mobile) gaming team at PokerStars and will have tremendous influence on our products.

For those not familiar with PokerStars, we are the largest real money poker company in the world, with over 70 percent market share. Last year, we generated over $1.1 billion in revenue and more importantly EBITDA (profits) of $524 million; a far cry from the struggles of most of my colleagues’ companies in the mobile and video game spaces. I lead the free to play team at PokerStars, which has seen tremendous growth in the last couple of years and has over 500,000 daily active players.

If you or a friend are interested in the consumer behavior position, send me a note at lloydm at pokerstars.com or apply directly to the job description. It will be a lot of fun. And for those who are not good at following HTML links, click below to get to the job description:

Job Description for Product Manager – Consumer Behaviour

I recently finished Michael Lewis’ most recent book, The Undoing Project: A Friendship that Changed the World and it motivated me to revisit Daniel Kahneman’s Thinking, Fast and Slow

. Lewis’ book describes the relationship between Daniel Kahneman and Amos Tversky, two psychologists whose research gave birth to behavioral economics, modern consumer behavior theory and the practical understanding of people’s decision making. He explains the challenges they faced and the breakthroughs that now seem obvious.

As I mentioned, The Undoing Project reminded me how important Kahneman’s book was, probably the most important book I have ever read. It has helped me professionally, both understand consumer behavior and make better business decisions. It has helped me in my personal life, again better decision making in everything from holiday choices to career moves. It helps even to explain the election of Donald Trump or how the situation in North Korea has developed.

In the Undoing Project, two things drove home the importance of Kahneman’s work. First, despite being a psychologist, Kahneman won the Nobel Prize for Economics in 2002. It is difficult enough to win a Nobel Prize (I’m still waiting for the call), but to do it in a field that is not your practice is amazing. The second item that proved the value of Kahneman’s (and his colleague Amos Tversky) work was the Linda Problem. I will discuss this scenario later in this post, but the Linda Problem proved how people do not make rational decisions, myself included. It convinced the mainstream that people, including doctors and intellectuals, consistently made irrational decisions.

Despite the value I derived from Thinking, Fast and Slow, I never felt I learned all I could from it. I found it very difficult to read, the exact opposite of a Michel Lewis book, and did not digest all the information Kahneman provided. Even when I recommended the book to friends, I often caveat the recommendation with a warning it will be hard to get through.

Given the importance of Kahneman’s work and the challenge I (and probably others) have had in fully digesting Thinking, Fast and Slow, I will be writing a series of blog posts, each one summarizing one chapter of Kahneman’s book. I hope you find it as useful as I know I will.

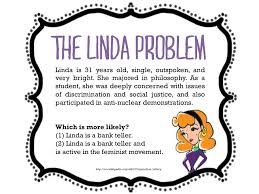

As discussed above, the Linda Problem is the research by Kahneman and Tversky that largely proved people thought irrationally, or at least did not understand logic. While I normally like to paraphrase my learnings or put them into examples relevant for my audience, in this case it is best to show the relevant description from The Undoing Project, as the Linda Project was a scientific study that I do not want to misrepresent:

Linda is 31 years old, single, outspoken and very bright. She majored in philosophy. As a student, she was deeply concerned with issues of discrimination and social justice, and also participated in anti-nuclear demonstrations.

Linda was designed to be the stereotype of a feminist. Danny and Amos asked: To what degree does Linda resemble the typical member of each of the following classes?

- Linda is a teacher in elementary school.

- Linda works in a bookstore and takes Yoga classes.

- Linda is active in the feminist movement.

- Linda is a psychiatric social worker.

- Linda is a member of the League of Women voters.

- Linda is a bank teller.

- Linda is an insurance salesperson.

- Linda is a bank teller and is active in the feminist movement.

Danny [Kahneman] passed out the Linda vignette to students at the University of British Columbia. In this first experiment, two different groups of students were given four of the eight descriptions and asked to judge the odds that they were true. One of the groups had “Linda is a bank teller” on its list; the other got “Linda is a bank teller and is active in the feminist movement.” Those were the only two descriptions that mattered, though of course the students didn’t know that. The group given “Linda is a bank teller and is active in the feminist movement” judged it more likely than the group assigned “Linda is a bank teller.” That result was all that Danny and Amos [Tversky] needed to make their big point: The rules of thumb people used to evaluate probability led to misjudgments. “Linda is a bank teller and is active in the feminist movement” could never be more probable than “Linda is a bank teller.” “Linda is a bank teller and active in the feminist movement” was just a special case of “Linda is a bank teller.” “Linda is a bank teller” included “Linda is a bank teller and activist in the feminist movement” along with “Linda is a bank teller and likes to walk naked through Serbian forests” and all other bank-telling Lindas.

One description was entirely contained by the other. People were blind to logic. They put the Linda problem in different ways, to make sure that the students who served as their lab rats weren’t misreading its first line as saying “Linda is a bank teller NOT active in the feminist movement.” They put it to graduate students with training in logic and statistics. They put it to doctors, in a complicated medical story, in which lay embedded the opportunity to make a fatal error of logic. In overwhelming numbers doctors made the same mistake as undergraduates.

The fact that almost everyone made the same logic mistakes shows how powerful this understanding is. It proves that our judgment, and thus decision making, is often not logical but does contain flaws. This understanding helps explain many things in life and business that sometimes do not seem to makes sense.

Once you understand how our judgment is biased, it can help you make better decisions. It can also provide insights into how your customers view different options and why people behave as they do. In future posts, I will explore all of Kahneman and Tversky’s major findings and how they apply.

I have always been interested in decision making and how people often are not logical in not only their preferences but even how they remember and look at facts. The most useful book I ever read was Thinking, Fast and Slow by Daniel Kahneman, (highly recommend it if you haven’t read it yet) and one of my favorite academics is behavioral economist Dan Ariely. Not only does Kahneman and Ariely’s research help you understand consumer behavior, it helps you understand your own decision making and, most importantly, mistakes most of us make.

A recent guest blog post on the Amplitude Blog, 5 Cognitive Biases Ruining Your Growth, does a great job of describing five biases that can greatly impact your business. While I will try to avoid just repeating the blog post, below are the five biases and some ways they may be impacting you:

A product manager may have driven a new feature, maybe a new price point on the pay wall. Rather than running an AB test (maybe insufficient traffic or other changes going on), they then review the feature pre and post launch. Game revenue per user increased 10 percent so they create a Powerpoint and email the CEO that there new feature had a 10 percent impact. Then the company adds this feature to all its games. The reality is that at the same time the feature was released the marketing team stopped a television campaign that was attracting poorly monetizing players. The latter is actually what caused the change in revenue. As someone who has known a lot of product managers, I can confirm this bias in the real world.

Two branded games are in the top 5 of new releases. All of the analysis is that branded games are now what customers are looking for. The realities is that the two games, totally unrelated, had strong mechanics and were just that lucky 10% of games that succeed. Allowing the Narrative Fallacy to win, however, you then put your resources to branded games, which are no more popular than before the launch of the two successful titles.

Again, for the example from the game industry. Let’s say you want to port your game to a new VR platform. You go to your development team and they say it won’t be a problem. You sign up for the project, give them the specs, six months later they still cannot get the game to run on the VR platform as they have no idea how to develop VR (this is a nicer example than some others I can remember).

As an example, you decide to analyze how your company has been calculating LTV. You look back at the analysis done the last two years and see how actual LTV tracked with projections at that time. You discover that you underestimated actual spend by 50 percent. Should be great news, will allow you to ramp up dramatically your user acquisition. Instead, when you present this data to your analytics team, they refuse to accept it, saying your analysis is flawed because you are not looking at the right cohorts.

Given that I want to keep this blog post under 500 GB, I will not list all the examples of the bandwagon effect I have seen in the game industry. Product strategy, however, is the most obvious culprit. When the free to play game industry started to evolve to mobile, everyone started porting its Facebook games over to mobile. Since Zynga and the other big companies were doing it, all of the smaller companies as well as newly funded ones also tried to bring the same core mechanics from Facebook over to mobile. Mechanics that worked on Facebook, however, did not work on mobile but companies continued doing it because everyone else was. Rather than identify the market need and a potential blue ocean, companies just joined the bandwagon.

The key to making the right decisions is not to assume you do not have biases, but always to be diligent in reviewing your decisions and making sure you are thinking rationally. All of these biases can lead to personal or company failure, so the inability to identify them can have extreme consequences.