Had the pleasure of being on Deconstructor of Fun podcast earlier this week to discuss the subscription business model as well as some other timely topics for the game industry. If you want to learn more about the subscription model (or developments at some game companies, listen to the podcast here.

Author: Lloyd Melnick

Why you are probably under allocating resources to retention

One issue I see repeatedly with game and gaming companies, and many other industries, is under-indexing their investment in retention versus acquisition and reactivation. While there is no evil plot to neglect retention, it is the most challenging part of the life cycle to determine ROI on investments.

With acquisition marketing, most successful companies have visibility into the CPI (or CPA depending on how you look at your UA efforts) they are paying and the LTV for those players. By comparing CPI and LTV, there is a clear ROI. Companies can then allocate resources to acquisition marketing as long as the ROI is above their needed return on capital. Also, as you are probably spending thousands or even millions of dollars per month on acquisition, optimizing that spend justifies additional resources (analytics, tools, etc.) as you want to get the most out of your spend.

Reactivation is similarly easy to quantify. You look at the cost of getting the player back and then how much they are likely to spend once they are back. Not only is it easy to calculate the ROI on reactivation spend, you can justify the investment because the revenue will be higher than the investment. No executive can argue with spending $1 to get $2. The only caveat with reactivation spend is ensuring you are not spending to bring back customers who would return regardless.

While retention is your most important KPI, it often does not get the same level of love because the ROI is much less obvious. You are not adding a user and revenue. You are not bringing back a lost customer. Retention, however, warrants more investment than every other part of the business combined.

Retention spend avoids spending $1 for $0.40

Every dollar you spend to retain existing players impacts your recurring player base. With acquisition marketing, even the best apps and games are lucky to see a 40 percent D1 rate (40 percent of customers who download the app return the next day). Thus, for every dollar you spend on a new player, only $0.40 or less is contributing to your product’s performance the next day. Given that a normal (though still good) D7 retention rate is 10 percent (1 out of 10 newly acquired players play on the seven days after downloading your game), you effectively only have $0.10 left from that $1 of spend still working for you.

Conversely, virtually every dollar spent on existing players is contributing to your product for days or months. A contest that encourages people to play more touches all your players and could impact their behavior over their lifetime. You are not losing 60 percent or 90 percent even before you can do a thorough analysis.

Retention spend can make the cost of acquisition less painful

The first subject everyone talks about at conferences (and even importantly at the bar during conferences) is how expensive it has become to acquire customers. Yet despite the money and resources spent on acquiring the player, the same effort is not made keeping and delighting the player.

Many marketing teams feel their job is done once the player is in the game (or has made a purchase) and thus their efforts are focused on acquisition. The true value to the company, though, is turning those new customers into a loyal player. While it is not solely marketing’s responsibility, it is a critical part of the equation. If marketing acquires a player for $5, they then spend $7.50 and churn, it may look like (and is) a marketing success as they have achieved a 150% ROAS (return on ad spend). However, if they could use retention marketing to have that player make $7.50 purchases every month for a year, the impact is 12X better than the acquisition spend. Moreover, the cost of getting that player to become a repeat customer is almost certainly not 12 times the acquisition cost, but a fraction of that cost. Thus the ROI is significantly higher.

Retention is not just about the product

At this point, many of my marketing friends are probably saying (or thinking) that retention is the responsibility of the product team, they have already done their job. Product and marketing are no longer two distinct functions. Companies like Facebook and Uber have blitzscaled because their products were also their acquisition channels (hence the term growth hacking), thus these products were the marketing. Conversely, product can only touch players when they are in the product (though they can build systems to bring customers back). Marketing, however, can impact players any time. The player may not have been in the game a week but you can still impact them by email, text, Facebook, Snapchat, television, blimp, etc. Retention is largely about triggers, reminding customers to use a product again, and marketing must work with product to ensure customers stay engaged.

A bird in the hand…

Optimal investment is not only about maximizing return but also managing risk. There is much less risk dealing with a known entity (an existing player) than an unknown. If you do take more risk, you should only do it if you will have higher return. A risk-based approach to allocating your resources also suggests that retention is a neglected investment vehicle. With new user acquisition, the new player is a question mark. They may fit your existing LTV curve or they might over/under perform. There is little information to base your estimate (largely the performance of other players acquired from the same or similar channel).

With an existing player, it is easier to estimate the impact of additional retention marketing. You have data on what they play, how often they play, what incentives impact behavior, etc. Based on this data, you can estimate accurately the return one additional marketing dollar will bring. These estimates will track much closer to actual results than new acquisition, especially with new channels, thus reducing the volatility of your return on marketing spend.

Retailers get it

While game companies, and many tech companies, disproportionally emphasize acquisition, retailers have learned over hundreds of years that their marketing budget is better optimized for retention. Most of the advertising and promotions from retailers are focused on bringing back existing customers, not getting them into the store for the first time. JC Penney or Target or Curry’s are not focusing their marketing on getting new customers, they are focused on driving behavior from existing customers. Sales are designed to optimize repeat purchasers and getting existing customers to spend more, very few are built to bring in new customers.

Amazon Prime is arguably the biggest factor making Amazon one of the most valuable companies in the world. Prime, however, does not get many people to try Amazon. Instead it converts existing customers into ones who spend more and are more loyal. The dynamics of retail are not that different than gaming, it is just that they have learned that there is a higher return in devoting resources to existing customers.

What to do

The value of retention marketing does not diminish the importance of acquisition or reactivation but you should design your structure so it is not neglected.

- Build your organization so that retention marketing is on an equal level. The head of retention should not report to acquisition. You should not have an EVP or SVP leading acquisition and a Manager leading retention. On the org chart, they need to be at comparable levels.

- Ensure you have KPIs in place measuring retention, what gets measured gets done. Virtually any company is monitoring daily its acquisition spend, CPI (or CPA) and ROAS. You need to be both measuring and reviewing regularly the success and growth that your retention team is driving.

- Rebalance your resources to ensure that you are optimizing your retention programs. Not only should you be running programs, but you need sufficient resources to build the campaigns, create the marketing collateral and analytic resources to review and optimize. Do not skimp on these resources for the quick thrill of acquisition or reactivation.

- As well as physical resources, you need to deploy sufficient budget to retention for long-term success. Start with a basic smell test. If you are spending $1 million a month on acquisition and your retention budget is $25k, probably something wrong. Try to align all your marketing spend with the understanding that retention drives significant value at lower risk.

If you do not focus on retaining players, any success will be short lived. To become great, your entire company needs to focus on keeping your customers.

Key takeaways

- While the primary focus of most game companies is user acquisition, retention marketing is often neglected. Retention marketing, however, is more important to a company’s prolonged success.

- For every dollar spent on acquisition marketing, at least $0.60 is lost the next day only 40 percent (at best) of players come back. Conversely, all dollars spent on retention marketing impact customers over their lifetime in your game.

- You should ensure your structure is built on optimizing retention as well as acquisition and allocate resources (both people and money) to reflect the immense opportunity with retention marketing.

Subscriptions: The new weapon in the game monetization arsenal

People in the game industry are continually asking about “a new business model” but they usually want new monetization techniques (ie. gatcha mechanic, piggy bank, etc.). Now, however, there is a real opportunity to disrupt the industry with a new model, subscriptions. I have been in the games industry since 1993 and in that time there have only been two new models, try-before-you-buy and free-to-play. Subscriptions may usher in the next era of gaming.

Try-before-you-buy was introduced in the early 2000s and perfected by Big Fish Games, who released via download a game every day that was free for the first hour and then the player would have the option of purchasing the full game. While the model did not have a huge impact on the traditional game companies (who were selling their product for a fixed cost in retail), it was blue ocean as it brought an entirely new demographic into gaming. For the first time, gaming was not dominated by teen age boys playing in their parents’ basements (or 30 year old boys playing in their parents’ basements) but saw an influx of female players, particularly older women.

Early in the 2010s the gaming industry experienced its greatest disruption. Free-to-play gaming gained traction in the US (and Europe) after dominating Asian markets. In this model, games were truly free and over 90 percent of the players would never spend a penny. The games, however, were built to get the most engaged players to spend to improve or speed up their gaming experience, and many of these players would spend tens or even hundreds of thousands of dollars in their favorite games. Social gaming companies, led by Zynga, gained millions of daily players, pulling them from other gaming or entertainment companies.

Free-to-play was truly disruptive. Household names like Atari, Acclaim and THQ (which had earlier reached over $1 billion in sales) went bankrupt. Zynga saw its valuation reach over $10 billion. Disney and Electronic Arts both spent hundreds of thousands of dollars to acquire companies in the space. The concepts behind free-to-play have grown to shape the video game space, even those old-school companies that still monetize with an upfront purchase use in-game monetization to drive their revenue growth.

Given the impact of free-to-play and the millionaires it, everyone has been looking for the next disruptive business model. Based on how other industries are evolving, subscriptions are likely to be the next disruptive model in the game industry,

How subscriptions are changing the world

While Asia provided a clue that free-to-play would disrupt Western video game markets, developments in other industries show the likelihood that subscriptions will emerge as a disruptive force. The largest retailer in the world (by market cap), Amazon, uses its Prime subscription service to lock in customers. Salesforce.com, the most important company in the enterprise software space, eschewed the high fixed fee model for a subscription model that left its established competitors in the dust. Adobe, the largest provider of graphics software, abandoned its old business model to move to a subscription model and is now valued at $135 billion. Netflix, the second most important entertainment company in the world (nobody is beating Disney for a while), gained its position with a subscription model. Even Disney is betting its future on subscriptions with Disney Plus.

Enabling this shift is a change in people’s attitude. Ten years ago, people would not pay for digital content and overall wanted to own things. People did not pay for music (remember Napster). People would buy a DVD or CD, even if they would only experience it once. The examples above (and the hundreds I left out) show that attitudes have shifted. Millions of people are willing to pay Spotify money every month without owning a song. According to the Reuters Institute, in the United States, the proportion of people ages eighteen to twenty-four paying for online news leaped from 4 percent in 2016 to 18 percent in 2017. Attitudes have clearly shifted.

Why subscriptions work

Subscriptions have succeeded because they better align customers with providers than other business models. Rather than the linear model of selling a product to a customer, the subscription model creates a dynamic where the company to please constantly its customers. As Tien Tzuo says in Subscribed, “companies that know what their customers want, and how they want it, will succeed over companies that spend a lot of time and effort creating a product they think is a good idea, then spend equal amounts of time and effort trying to persuade people to buy it.”

Further driving the success of the subscription model are the benefits it has for the provider. Subscriptions allow companies to start the month (or year) with a guaranteed base of business. Rather than having to estimate how many units you will sell, you look at your subscriber base and can accurately forecast your revenue. This stability allows companies to market aggressively, invest in new content, etc., as they can predict cash flow.

The subscription model also aligns companies with their customers. As Tzuo writes, “instead of thinking about reseller margins and unit sales, [companies are] thinking about subscriber bases and engagement rates.” Companies driven by a subscription model have direct ongoing relationships with their customers. They no longer have to segment customers, they now have individual subscribers. With the industry leaders (Amazon, Netflix, etc), every subscriber has their own home page, their own activity history, their own red flags, their own algorithmically derived suggestions, their own unique experiences. And thanks to subscriber IDs, all the boring transactional point-of-sale processes disappeared. As companies can never be too close to their customers, subscriptions create the loop that makes customer intimacy a reality.

Will subscriptions work in the game industry

Now that we agree that subscriptions are a great opportunity overall, will they work in the game industry. First, many game companies already are using this model. According to a great blog post by Google, they have seen global growth in game subscriptions of 70 percent year over year. Second, it is working. According to the post, game companies that have integrated subscriptions experience 20 percent higher retention. They also have seen higher overall monetization. Finally, subscriptions offset risk in developing and launching new content. According to Tzuo, “regardless of whether a show is successful or not, investing in sharp new content helps Netflix to both (a) attract new subscribers and (b) extend the lifetime of its current subscribers. Those shows don’t go away! Together, they’re increasing the overall value of the portfolio. They are instrumental in driving down customer acquisition costs (as more subscribers sign up) and increasing subscriber lifetime value (as more subscribers stick around for longer).”

How you should implement subscriptions in games

While subscriptions are an exciting opportunity, success with the model will come down to execution. Just as hundreds (or thousands) of game companies failed to implement successfully free-to-play, succeeding with subscriptions is more difficult than adding another package to your purchase page. There are several core concepts in building a product that leverages subscriptions.

Subscriptions need to be about access

The biggest challenge, and most common mistake, game companies face is what to provide for the subscription fee. The easy answer is virtual currency, after all it is what customers are willing to pay for with in-app purchases. The easy answer is wrong. As stated in the Google post, “it’s important to move away from the mindset that subscriptions are just an auto-renewal mechanism for discounted IAP. Instead, subscriptions need to be thought of as offering highly-retentive long-term access to content, rather than the one-time situational purchase of content offered by IAP.”

Successful subscriptions are about giving players access to content and special benefits, access that can be gained or lost. In a social casino, it could be access to new slots or unique table games. In a game like Archero, it could be access to special levels or powers. The benefits could also be exclusive tournaments, special avatars or unique in-game events. The key, though, is not limiting (or even relying) on giving players virtual or premium currency but access to a premium experience.

Keep it simple

One of the core principles in creating successful products is to focus on simplicity, which is often very complex to do, and subscriptions are one area where it is easy to fall into the complexity trap. Companies with very successful subscription offerings have very few options.

If you offer customers too many options, it is likely to overwhelm them and preclude them from choosing any of the options. This concept of cognitive load is critical to the success of many products, from games like slots to apps like Uber. Given that the human brain consumers 20 percent of the body’s energy but only is 2 percent of the body’s mass, it is important to understand that people will subconsciously work to reduce the amount of energy the brain is using.

Cognitive load is how much info people are processing at any one time. Cognitive load is tied to working memory, the more information in that short-term memory the higher the cognitive load. As cognitive load increases, consumers are less likely to make a purchasing decision.

With subscriptions, this is directly tied to the offerings. If a player has different options ranging from the term of the subscription, monthly costs, benefits levels, they are likely to choose none. For example, you might offer people a month-to-month, 3-month-, 6-month or 1-year plan, with pricing at $4.99, $9.99, $19.99 and $49.99, each with different benefits. Rather than the player finding the one that optimizes their utility (to use an economist term, or makes them happiest, to use a human term), they are more likely to shut off and just pass on the offerings.

Instead, offer them one or two (at most) options. It can be a regular subscription or a premium one (additional benefits) or a short-term plan and an annual plan. You do not see Netflix offering ten different types of subscriptions. The key is make it very easy for the player to understand the value and choose between the two plans and whether or not to subscribe.

Keep it honest

One of the reasons subscriptions took so long to be commonly accepted is that until recently they were part of a sleazy industry. Companies would trick customers into signing up for a subscription, then make it very difficult to cancel the subscription. They might let you sign up easily, then require you to call them to cancel at a call center open one hour a week every second week. Even then, the agent you spoke to would do everything humanly possible to keep you from cancelling, creating an awful experience. These practices soured people overall on signing up for subscriptions. With social media and sites like TrustPilot, word quickly gets out of deceptive subscription tactics.

Preventing customers from leaving or tricking them into subscribing is not only unethical, it is bad business. One of the fundamental values that subscriptions create for a business is the connection with the customer. It forces the company to ensure every month it is creating value for the customer and that is why the customer renews or maintains the subscription. Everyone on the product team looks at new content and features and judges whether it will help retain customers and bring in new subscribers. While scamming customers may bring short term gain, it is the customer connection that subscriptions create that leads to great companies like Amazon, Netflix, Spotify, etc.

The best companies use subscriptions to improve their underlying business. Tien Tzuo writes in Subscribed that “the smart [companies] realize that if they really want to retain their subscribers, they need to focus on building a great service, without relying on lame tricks like hiding the cancel button.…Make it easy for customers to leave if they want to. You can certainly ask them why they’re leaving, or try to win them back, but don’t get in their way—the digital equivalent of blocking the exit with a hulking security guard. When you build subscriptions into your game, let customer value drive the offering rather than tricks on keeping customers from cancelling.

Build a loop

A successful subscription plan should be tied to engagement in the underlying game. The more a customer plays the game, the higher the value of the subscription. According to the Google post, “in mobile games’ subscriptions design, some offer a booster or bonus points, to reinforce the action of ‘play.’ Some create a durable good, such as a permanent building or character, that levels up as a player remains a subscriber for a longer period of time. In these cases, the desired action is “continue to subscribe.” In other cases, subscribers get bonus premium items, currency or points to reinforce the action of in-app purchases.

Looking outside the game industry, airlines have done a good job of creating a loop around their frequent flier programs. With frequent flier programs, members improve their status by flying more or buying expensive tickets, such as business class. According to the Google post, “the ‘earn’ criteria here — flying or spending — is precisely the desired customer actions that the airlines want to reinforce.”

Evolve benefits

Another important element of a successful subscription program is that benefits evolve. According to Google, “as the players invest more in the game, whether it’s with their time, skills, or other IAP, the subscription benefit also compounds.” Thus, the player can unlock more sophisticated content or new challenges that would not have been relevant for them earlier in their experience.

Celebrate VIPs

VIPs are the core of virtually any social game’s success. Most free-to-play games generate 60-90 percent of their revenue from the top 1 or 2 percent of players. Many product managers have avoided subscription programs because of concern on how it would impact VIPs. If a player can subscribe to a VIP program for a fixed sum, the concern is that would put a cap on how much the VIP would spend in the game.

This concern leads back to the first point on subscription design, that is should be about access, not a replacement for existing purchases. Thus, the subscription plan might give the VIP access to slots they would love to play but not chips to play those slots.

When thinking about your VIPs, do not forget they are already VIPs. If someone is spending significantly in your game, do not try to take another $5 or $10 from them every month. Instead, turn the subscription into a celebration of their VIP status. Give them a free subscription, the goodwill will be worth much more than the short term revenue you would generate from forcing your VIP to purchase a subscription.

Use subscriptions to drive acquisition and convert players

In addition to driving monetization and engagement, subscriptions are a great way of increasing retention they are also a strong acquisition tool and powerful CRM element early in the product life cycle. First, an offer of a one or three month complimentary subscription can entice a potential customer not only to try your game but invest time to learn about your product.

Second, subscriptions can help convert players into customers of in-app purchases. They provide a way to let players see and test the spectrum of in-app offerings. According to Google, “Scopely’s game Wheel of Fortune frames its subscriptions offer as an all-access pass. These subscriptions feature exclusive rewards that a potential buyer would want in addition to a sales discount. Surfaced right after the first-time user experience (FTUE), with benefits such as ‘more energy, this subscription aims to increase these new buyers’ in-game engagement, and cultivate a habit of playing regularly and investing in their future gameplay.”

Third, subscriptions can increase virality, helping your existing users bring in new customers. Campaigns that let your subscribers give free months to their friends, and get free months themselves, are very effective at driving new user acquisition. For example, a promotion where a player can gift a new player three free months, and get a free month for every new player who signs up, helps you acquire players with the only cost being the lost subscription revenue of your advocate.

Making subscriptions a reality

Rather than being a follower, future successful game companies will push forward with subscriptions and help disrupt the industry, not react to the disruption. By focusing on execution and building a strong subscription offering, it is likely we will see the next Netflix or Spotify.

Key takeaways

- Many industries are evolving from a discrete purchase model to a subscription model. From retail (Amazon) to music (Spotify) to entertainment (Netflix) to enterprise software (Salesforce.com), the subscription model is redefining winners and losers. The game industry will eventually succumb to the same forces.

- To create a successful subscription program, the offering needs to center around providing customers with unique access and benefits, not replicating what they get when making in-app purchases.

- Successful subscriptions also need to build an honest relationship with players, provide simple options, create a loop where subscribers enjoy more benefits by playing more, appeals to new potential customers and rewards your VIPs.

Are the glory days of social casino over? Probably!

While revenue in the social casino space continues to increase (a streak that has not been broken since the first days of Zynga Poker and Slotomania), dark clouds on the horizon have started to dampen the enthusiasm. Most social casino companies would not publicly disclose that they are expecting growth to slow (or reverse) but unspoken indicators are bearish.

Stagnant player growth

The greatest threat to the social casino industry is that the user base is not growing. Over the past couple of years industry revenue has continued to increase but active players has remained virtually stagnant. The revenue growth has been driven by certain companies (particularly Playtika) becoming increasingly adept at growing revenue per customer, especially among their VIPs. At some point, however, social casino operators will hit a ceiling as VIPs cannot and will not spend more.

Actions show that the top companies do not believe in the space

While no social casino operator has publicly warned about the challenges they are facing, their actions speak more loudly. Playtika, the largest social casino company, acquired Seriously last month, after acquiring Wooga last year.

Huuuge Games, the biggest success story in the social casino space in the last three years, launched a publishing arm. Critically, it is focused on hypercasual and traditional social games (such as Traffic Puzzle) rather than social casino. Given how involved Huuuge is with social casino, if it expected tremendous growth it would almost certainly be focusing its efforts to further increase market share in this space.

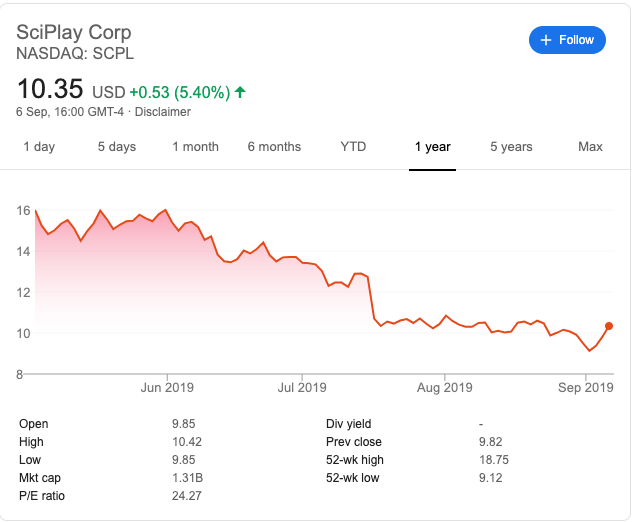

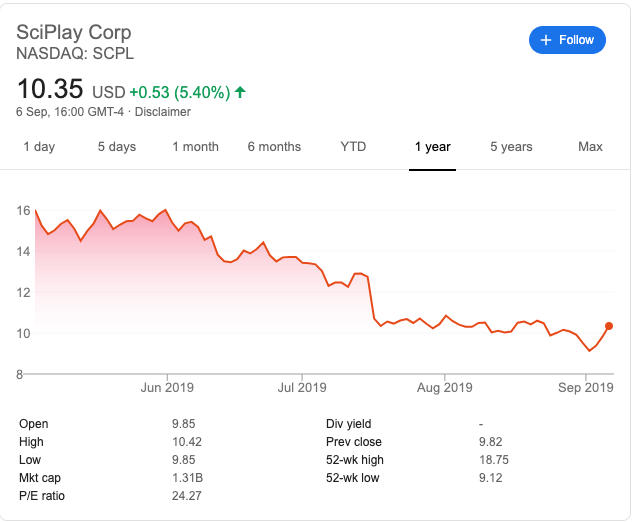

The public markets are also talking

While social casino operators are showing how they look at the industry through their actions, the public markets also show how investors view the opportunities in social casino. The first pure play social casino IPO, SciPlay (the social casino operations of Scientific Gaming), has seen its share price drop from $16 when it went public in May to $10.35, losing over 30 percent of its value.

From 2015 to 2017, virtually every Zynga’s earnings call highlighted its social casino division. Initially, it focused on the growth of its slots products (primarily Hit It Rich!), which was largely the only bright spot for the company. Not only did it tout the success of its slots products, but the big IP licenses it was signing for future products (such as Willy Wonka). The calls then incorporated Zynga’s success with Poker, which experienced a renaissance. Very noticeably, over the last year, Zynga has downplayed or even ignored the role of social casino in its growth projections. In part, this is due to the success it has experienced with recent acquisitions (and the struggles it has experienced recently in the social casino space), but it also highlights that investors are not very receptive to initiatives in the social casino space.

Again, actions speak louder than words. While investors are not perfect (The Big Short, anyone), they are focused on optimizing return and look across a broad spectrum to find the best opportunities. The lack of appetite for social casino shows that investors no longer think social casino is easy money.

The other looming risk

Another cloud dampening the prospects for social casino is real money gaming. The US is disproportionally important for the social casino industry, it derives a much higher percentage of total revenue (over two thirds) than other areas of the video game industry (which derives over 50 percent of revenue outside the US). While there are too many factors to determine causality, the US is the only major social casino market where real money online casino is largely illegal. Thus, many customers who would normally play in a real money environment can only get their online casino experience through social casino.

Eventually, as real money casino play becomes legal in more US states, it represents an existential risk to the social casino industry. This risk is not an immediate one, legislation has to be approved on a state-by-state basis and I do not expect a significant number of states to approve legislation until 2022-2023 at the earliest (sports betting is a very different phenomenon). Investors and companies, however, do look beyond the next few years to determine their best opportunities and real money gaming is an acute part of that equation.

What social casino companies should do

First, innovate. While it sounds trite, innovation is the key to revitalizing the sector. The industry (and many other parts of the game industry) has been driven by copying what is already working, trying to do it a little better and continued optimization. They are thus relying on fewer players to generate more revenue. Coin Master is a great example of how a company can generate hundreds of millions of dollars in the social casino space by breaking the mold and creating a casino product for new customers. Finding Blue Ocean opportunities using casino mechanics can reverse the dynamics threatening the industry.

Second, embrace Real Money gaming. While Real Money is a risk, it is also potentially salvation. Land based casino companies largely resisted social casino for years (one particularly reactionary one still does) only to find that customers who also play social casino have a higher lifetime value. MGM’s relationship with Play Studios (MyVegas) has driven millions of dollars of value to MGM, displayed by MGM’s increasing its support (actions speak louder than words).

While the relationship between social and real money online has not yet been proven, the size of the opportunity should generate more attention from social casino operators. Real Money online gaming, a $54+ billion industry, dwarfs social casino. If social casino companies can learn how to capture a portion of that revenue (and player base), it can exceed greatly the growth rates of the past.

Key takeaways

-

- Despite growing every year since the first social casino products launched, the industry faces significant risks. There are highlighted by recent growth driven by improved monetization of existing players rather than appealing to new customers.

- Further corroborating this problem is how leading social casino companies are looking outside the space for acquisitions while investors are showing little interest in social casino.

- To combat these trends, social casino companies need to look for Blue Ocean opportunities (use social casino mechanics to appeal to new customers) and leverage the roll out of real money gaming.

How to upsell and cross sell more effectively

Retailers derive significant value from upselling and cross-selling customers but mobile and social game companies are yet to master this opportunity. The cost of acquiring customers, particularly paying customers, is high so it is vital to get as much value as possible from these customers. It is also more cost effective, as Marketing Metrics stated it is 50 percent easier to sell to existing customers than new ones.

First, it is important to understand the difference between upselling and cross selling. Upselling is getting a customer to purchase more of an item they are already buying while cross selling is convincing them to purchase complimentary items.

Starbucks presents examples of both upselling and cross selling. If you are about to buy a Grande Latte and the cashier suggests a Venti Latte, they are upselling. If they then ask you if you want a Cake Pop with your Latte, they are cross selling.

In the social gaming space, both are possible. If a player is about to buy 5,000 chips for $10, you can upsell by offering them another 1,000 chips for $1. You can cross sell by also suggesting they pay to unlock five exclusive slot machines to use their new chips in for another $10. You can also cross sell them into another game.

A recent post, 3 Slick Upsell & Cross-Sell Methods to Boost Revenue + Profit by Sam Hurley, , does a great job of explaining the three areas you can deploy upselling and cross-selling.

While browsing

When a customer is playing your game or wandering in a casino it is a perfect time to cross sell them with potential purchases. Their game or browsing activity is an opportunity to show them how they can have a better experience by monetizing. At this critical stage in their journey, they may not be aware of your other offerings, or plan to make a purchase. As Hurley writes, “while customers browse your digital properties, product or service bundles should be presented as super helpful add-ons.”

In social casino, one of the most impactful developments was integrating progressive jackpots with an upsell mechanic. Players can enjoy a slot (browse) and then be presented with an offer to bet higher and have a chance to win a huge progressive jackpot. Only with the higher bet, which requires monetization, can players enjoy the progressive jackpot. In real money casino, this is an even clearer upsell, as players need to play at a higher stake (spend more) to have the chance to win more.

One critical element to keep in mind when players are browsing/playing, is that the offer needs to be relevant. If somebody is playing slots, a promotion to sports bet is unlikely to be successful. Instead, try to get them to spend more on the slots and give them a sports betting offer during the purchase (see below).

On paywall

The second great opportunity to upsell and cross sell a player is when they are in the process of purchasing. First, you can upsell by offering them an add-on. This add-on can be additional chips or currency at a discounted price or a different virtual item in the game (the upsell).

This is also a great opportunity to cross sell. When someone is making a purchase, you can give them something of value in another one of your products (the cross sell). This can be free chips or tournament tickets in the other product, access to a special VIP area, sneak peak or exclusive content (which they would not want to lose).

For the purchase event upsell/cross-sell to be most effective, you should imbue a sense of urgency and scarcity. If it is an offer to purchase more, make it a limited time offer only available to X players. With cross sell, it is even more powerful. If you have a poker game and give someone a key that expires in 24 hours for an exclusive slot in your casino product, that is a powerful incentive for them to try your other game.

To optimize the efficiency of these purchase events activities, Hurley recommends several key elements:

- Keep it tidy. Don’t clutter the deposit page and overwhelm customers (this could actually lose business, instead of gaining it).

- Keep it simple. Tell customers exactly what they will get via upsells and cross-sells, concisely and considerately.

- Keep it welcoming. You don’t want your customer to feel they are buying a used car. Hurley recommends “Customers also bought…” instead of “Add these to your cart, now!”

- Keep it relevant. The better the alignment, the greater your conversion rate and order value.

After purchase

Once you have gotten a player to monetize, it is the optimal time to turn them into a repeat customer. According to Hurley, post-purchase upsell and cross sell has the highest conversion rate of any type of upsell. Look at the purchase as the beginning of a never ending funnel, the beginning of the Paying Customer Journey.

Once a customer has made a purchase, you can both present upsell and cross sell offers. Allow them to make an additional purchase for a limited time or give them loyalty points, where they earn even more by making another purchase. It is also a great time to present your other products, by buying chips in our slots product, why don’t you try our video poker experience.

There are four primary ways to present the post purchase cross or upsell opportunity:

- Once someone has made a purchase, set up a drip email marketing campaign tailored to that player. Make follow on offers based on how they used their initial purchase and the size of the purchase.

- Customer support (across all channels) is another chance to upsell and cross-sell your customers, but ensure your CS reps have access to the purchase information and do not turn into cheap salespeople (their primary objective is to keep your customers happy).

- Push notifications, simple mobile message saying your recent purchase entitles you to a 25 percent discount right now.

- Receipts. Include an offer when you send a receipt to a player for a purchase (even if made through the app store use it as an opportunity to send a receipt). Receipts have a much higher open rate than other emails (71 percent versus about 17 percent) and are more likely to be retained by your customer. Include in the receipt a discount off the customer’s next purchase.

Keep upsell and cross sell top of mind

Given the high ROI of upsell and cross sell promotions, you need to integrate it into all elements of product development and CRM. Think of the various customer touchpoints and how you can integrate upsell and cross sell.

Key takeaways

- It is 50 percent easier to sell to existing customers than new ones, so you should focus efforts on increasing the size of purchases by your current customers (upsell) and getting them to purchase more of your products (cross-sell).

- There are three elements of the customer journey where you can cross-sell and upsell, when they are playing your game (browsing), during the purchase and after the purchase.

- Post purchase is the most effective time to upsell and cross-sell, you can offer your customers a discount on their next purchase or an incentive to try one of your other games. This can be done via email, push notifications, your CS team or by sending a purchase receipt that incorporates an offer.

How to change bad habits, the neuroscience way

I have written repeatedly that people do not often behave rationally, and Tali Sharot’s book, An Influential Mind,helps show that much of this irrationality is hardwired into our brains. Sharot writes how our brains are “hard-wired”, which makes it challenging to break bad habits. Instead, by understanding how we our brain works, we can adjust both our own bad habits and help others.

We are all hedonists

Not much of a surprise but people are wired to strive for pleasure. The corollary, and more important takeaway, is that this principle cannot be unlearned. It is a waste of time and resources to try to get people (or yourself) not to pursue pleasure. Instead, it is best to channel this pursuit in yourself and in others.

When motivating your employees or potential customers, it is much stronger if you do it by offering them “pleasure.” When offered a reward, the brain kicks into gear, and people experience quick and alert responses. If the potential result is something bad, the brain turns sluggish, and their responses suffer. Thus, the carrot is better than the stick in driving optimal behavior.

Control is important

Having control of one’s life is a very instinctual desire, it provides happiness. People are happier when they are in control. Sharot points out the same situation exists in the office. If you want happier employees, make sure they have input in making decisions that touch their daily work.

Studies have shown people are happier, and even live longer, if they have to participate and work for something rather than be served. Elderly people did better at a care home where they had to prepare their own meals. In the work environment, it is often superior to have the team that needs to create a product or develop software involved in crafting the product specifications, rather than just handing them the final spec and asking them to build it.

Humans are not flexible

One negative way of thinking that Sharot attacks is how once someone has made up their mind, they tend to ignore contrary information and forge ahead regardless. I have experience (all too frequently) how a colleague is sure they have the right strategy or process, does not listen to others, and then fails. This happens even when everyone else sees the negative outcome. It may have been launching a new product that will have no demand or analysing data incorrectly and making decisions based on that analysis, then when the product is launched or project is done, it turns out to be an abject failure. Upon retrospection, the question is asked how did this mistake happen.

Research has found this inflexible decision-making is programmed into the brain. In an experiment, brain activity of participants was measured during the decision-making process and brain activity dropped significantly upon receiving bad information (that is, information that was contradictory to their original decision). This shows that when people commit to a decision, there is a natural defense mechanism that helps them avoid learning it is a bad decision.

To combat this defense mechanism, Sharot shows it is better to focus on presenting new factual information rather than arguing against the preconception. If you are trying to convince somebody their mobile game project will fail, do not attack the concept or the demo but present new information. Talk about new games on the market or new options. Do not try to discredit the belief, as people become resistant and defensive, often getting stronger in original idea. Instead, provide different, positive information.

Moods are contagious

The moods of others around you helps determine your mood. Based on MRI scans during political speeches, researchers learned that listeners often feel connected to the rest of the audience. This learning shows why people at a rally often react the same at particular points of a speech. Other research showed that negative posts on FB lead to more negative posts, while the inverse is also true. Good and bad moods are contagious, people’s brains synchronize. Their brains are connected, so moods are contagious.

There are several implications of contagious moods:

- In a workplace, it is critical to maintain the mood and morale of your team. If several people on the team (or company) turn negative, it is likely to infect the entire organization.

- Negative social media sentiment about a product could not only turn a few people against it but create a negative overall perception.

- On a personal level, one or two family members can put the entire family in a good or bad mood, especially if they bring experiences from work or school home with them.

Entertainment trumps information

Related to the pursuit of pleasure, people pay more attention to entertainment than they do important information. Politics provide a great validation of this concept, Trump has tens of million Twitter followers because his tweets are entertaining. More people view a video of Congresswoman Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez dancing on a roof than discussing healthcare.

Another great example is the safety warnings on airplanes. It is probably more important to know what to do if there is an emergency landing than if you can reach the next level on Clash, but which one do most people focus on?

The lesson when building a product or game is that most tutorials will fail, instead people need to learn while being entertained. It also impacts how you communicate, an email or pop up listing benefits or features is not as effective as a fun GIF.

There is also a workplace impact of preferring entertainment to information. Sharot discusses that it might be easier to resolve a workplace conflict with a fun, novel solution rather than a lecture on the right way to do things.

Understanding the brain helps motivate yourself and others

The better you understand how the brain is structured and people’s motivation, the better you can interact with your family, colleagues and customers. Some of the most robust methods encompass remembering that everyone is motivated by pleasure seeking and reward and that people like to feel in control.

Key takeaways

- Our brains are “hard-wired”, which makes it challenging to break bad habits. By understanding how we our brain works, we can adjust both our own habits while helping others be more productive.

- People’s brains are designed to seek pleasure. Related to the pursuit of pleasure, people pay more attention to entertainment than they do important information.

- Having control of one’s life is a very instinctual desire, it provides happiness.

Why Real Money Skill Based Gaming is Doomed

With computers now beating the best players in poker and eSports, the raison d’être for gambling on skill based games is gone. Earlier this year, Google’s DeepMind Artificial Intelligence (AI) defeated two pro-gamers at StarCraft II. While the AI’s victory did not garner much attention, people are getting used to AI beating humans, it has profound implications for part of the real money gaming ecosystem. Coupled with Libratus beating professional poker players in No-Limit Texas Hold’em and previous AI victories in Go, Chess and other games, it is clear computers already can beat humans in most skill based games and will almost certainly conquer the rest of gaming in the near future.

I will leave the implications of powerful AI on society to the Elon Musk’s and Neil deGrasse Tyson’s, but it is important not to underestimate the impact on the electronic gambling industry. This type of AI will, faster than expected, make gambling on skill based games irrelevant.

Everything takes longer than expected but than happens at a more massive scale

In many ways, people have been lulled into a false sense of security because AI has not had a significant impact on gambling, yet. Bill Gates, however, once pointed out that transformational technologies normally take longer than expected to become widespread but once they do have a far greater impact than anticipated. Personal computers followed this pattern, they were a fringe product for years and people started to dismiss them as a fad. Then almost instantaneously they found their way into all parts of life (thank you Windows) and even your grandmother was using one to check her investments. Similar phenomenon occurred with cell phones, drones, streaming video, etc.

AI is following the same pattern, particularly in skill based games (chess, poker, go, StarCraft, etc.). It is going from fringe applications and projects that take years to quick iteration and AI that is superior to humans across many game variants. As the underlying algorithms get stronger, human players will no longer hold an advantage in any skill-based game. More importantly, the tech will go from computers only owned by huge research groups to devices or apps that normal individuals can get cheaply, just as the tech once needed to send a man to the moon is not as powreful as that in a common smartphone.

Doesn’t have to be best

It will not even take the time needed for optimal AI algorithms to become ubiquitous to impact skill based gaming, average AI can beat most players. While beating the top players in StarCraft or Go generates headlines, most people do not play at the level as the top players. Thus, even a sub-optimal algorithm can beat the majority of players. Once people realize they are unlikely to win because there are good algorithms everywhere, they will have no incentive to bet (very few people outside of Browns fans bet on sure losses). If everyone can get a device or program that let’s them play a skill-based game near optimally (but not perfectly), it will still mean that 90+ percent of people will lose regularly. Even those under the delusion they are in the top 10 percent will give up after repeated negative reinforcement.

Impact will be far reaching

As with other technologies, people often do not realize how broad the impact of AI will be. Initially, people will not want to wager on any Player vs. Player skill based game, because AI could augment the opponent. This problem will then extend to betting on any skill-based game, if the human cannot beat AI it is pointless to predict who will win.

The only exception will be at live events, from a Chess Tournament to a Live eSports Tournament. As long as the event can be controlled to limit or prevent AI (which I do not believe will always be possible), people could still wager on these live events. However, as more events move online (Twitch), this will be a small opportunity.

Social casino is not immune

The knee jerk reaction is that AI will negatively impact real money gaming but have a positive effect on social (free to play) casino, the reality is social casino will bear the same negative consequences. Players in social casino are also competing against other players and when AI makes it impossible to win regularly, the appeal of Player vs. Player social casino games will also decline. Recently Zynga saw a significant negative impact from bots in Zynga Poker, one of the largest poker games in the world. The impact on social games like Zynga Poker will get worse as AI becomes more prevalent.

You cannot stop the inevitable

Companies have learned repeatedly, often the hard way, that you cannot stop progress but seem to think they can. Taxi companies fought pitched battles against Uber in courts and with protests but the successful ones adapted their business to compete. Travel agents complained to the government and providers but only the ones who reimagined their businesses survived. While some companies have slowed change, they never stop it and leave themselves in a poor position to compete.

Where the real opportunity exists

While AI will negatively impact the existing gambling space, these types of challenges always create opportunity. Gambling is simply another form of entertainment so the trick is for companies relying on skill based gambling to pivot and provide another entertaining option for their customers.

- Maybe turn poker or backgammon into a fixed odds challenge against a computer.

- Pivot the business model to a subscription model so that there is no benefit to winning (and thus no benefit to using AI), especially viable for free-to-play.

- Use the great advances in virtual sports to replace traditional sports betting by offering people 24/7 events to bet on.

- Have people gamble on computer vs. computer sporting events (i.e. an EA Fifa World Cup).

- Create gambling that is based on individual skills (the quality of a drawing, the ability to solve math equations, etc.), player versus themselves.

- Take traditional casino games and adapt them for the mindset of skill-based players.

The point is you need to be creative and find a new way to entertain your customers.

Key takeaways

- With computers now beating the best players in poker and eSports, there is no reason for gambling in skill based games to exist.

- The proliferation of AI in skilled base games will take longer than predicted but when it happens will be much broader than anticipated and companies won’t be able to prevent it.

- Instead, successful gambling companies will understand they are providing entertainment and find new ways to delight their customers.

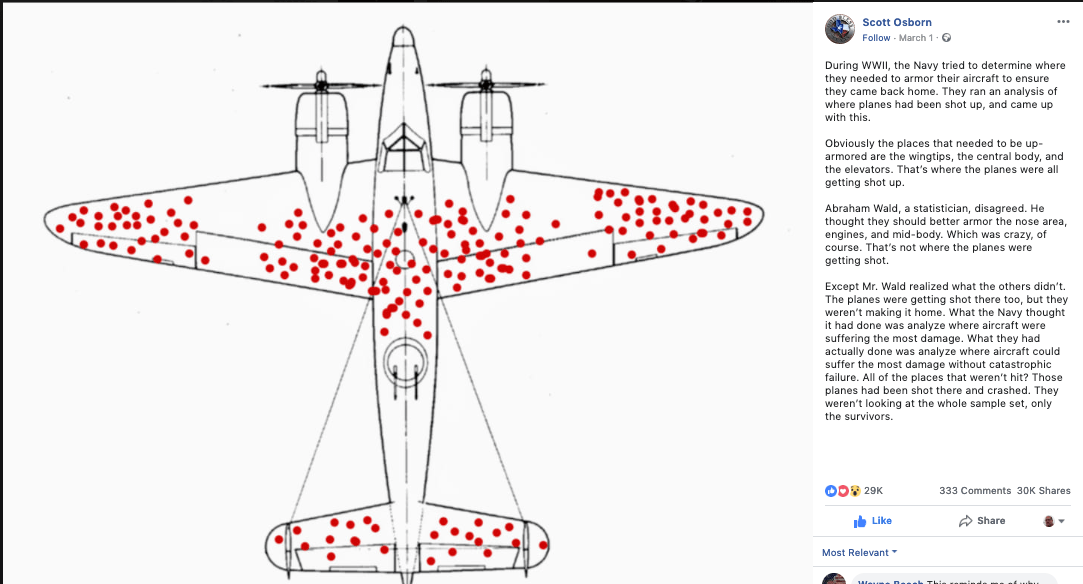

How to overcome survivorship bias

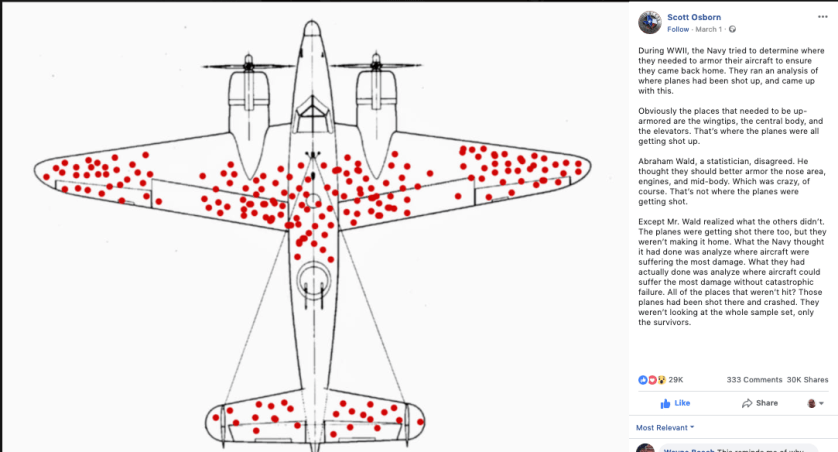

A few months ago I shared a story and post on Facebook about survivorship bias and was amazed how often it was liked and shared. It also highlights the risk of survivorship bias in the gaming and gambling space. The image and blurb told the story how the navy analyzed aircraft that had been damaged and based future armament decisions on where they had received battle damage, thus they were going to increase the armor on the wingtips, central body and elevators. These were the areas that showed the most bullet holes.

One statistician, Abraham Wald, the founder of statistical sequential analysis, however fortuitously stopped this misguided effort. According to Wikipedia, “ Wald made the assumption that damage must be more uniformly distributed and that the aircraft that did return or show up in the samples were hit in the less vulnerable parts. Wald noted that the study only considered the aircraft that had survived their missions—the bombers that had been shot down were not present for the damage assessment. The holes in the returning aircraft, then, represented areas where a bomber could take damage and still return home safely. Wald proposed that the Navy instead reinforce the areas where the returning aircraft were unscathed, since those were the areas that, if hit, would cause the plane to be lost.”

Survivorship bias is universal

Survivorship bias occurs everywhere. If you are a poker player, you may have a hand of three of clubs, eight of clubs, eight of diamonds, queen of hearts and ace of spades. The odds of that particular configuration are about three million to one, but as economist Gary Smith writes in Standard Deviations, “after I look at the cards, the probability of having these five cards is 1, not 1 in 3 million.”

Another example would be professional basketball. If you look at the best professional basketball players, a high percentage never went to university for more than one year. From this information, you (or your teen son) may infer the best path to the NBA is going to university for one year or less. The reality is that there are millions (if not billions) of people who went to university for less than a year and never played in the NBA (or even the G League). The LeBron Jameses and DeAndre Aytons are likely in the NBA despite playing less than a year in college due to their great skill, not because they did not go to university for more than a year.

As an investor, survivorship bias is the tendency to view the fund performance of existing funds in the market as a representative comprehensive sample. Survivorship bias can result in the overestimation of historical performance and general attributes of a fund.

In the business world, you may go to a Crossfit gym that is packed with the owner making a great living. You decide to leave your day job and replicate his success. What you did not see is the hundreds of Crossfit gyms that are not profitable and have closed.

The problem exists in gaming

You often see survivorship bias in the gaming and gambling space. People will look at a successful product and select a couple of features or mechanics they believe have driven the success. They then try to replicate it and fail miserably, only to then wonder why the strategy did not work for them. What they fail to analyze is the many failed games (for every success there are at least 8-10 failures) because they do not even know they exist. The failed games may have had more of the feature you are replicating. Getting a star like Kim Kardashian is a great idea if you only look at Kim Kardashian: Hollywood, but if you look at the hundreds of other IPs that have failed your course of action might be very different.

Survivorship bias can also lend its ugly head when building a VIP program. You talk to your VIPs and analyze their behavior, thus building a program that reinforces what they like about the game. What you neglect, however, is that other non-existent features might have created even more VIPs.

In the gambling space, you may look at a new blackjack variant that is doing great and build a strategy around creating new variants of classic games. What you did not see is all the games based on new variants that have failed.

Avoiding survivorship bias

Looking simply at successes, or even failures, leads to bad decision making. When looking at examples in your industry or other industries, you need to seek out both the successes and failures. With the failures, you need to make sure they are the failures (not the airplanes that returned shot up but the ones that were destroyed). You also should not use others successes or failures as a short cut to robust strategy decisions. You need to analyze the market, understand your strengths-weaknesses-opportunities-threats (SWOT) and do a blue ocean analysis. Only then will you build a strategy that optimizes your likelihood for success.

Key takeaways

- In WW2, by analyzing surviving aircraft the US navy almost made a critical mistake in adding armor to future airplanes. The planes that returned were actually survivors, while it was the planes that were destroyed that showed where on the plane was the greatest need for new armor. This phenomenon is called survivorship bias.

- This bias extends into the gaming and gambling space, as companies analyze what has worked in successful games but do not know if it also failed (perhaps to a greater degree) in products that no longer exist.

- Rather than just looking at survivors or winners to drive your strategy, you should do a full SWOT and Blue Ocean analysis, that is the strongest long-term recipe to optimize your odds of success.

The Making of a Product Management Case Study

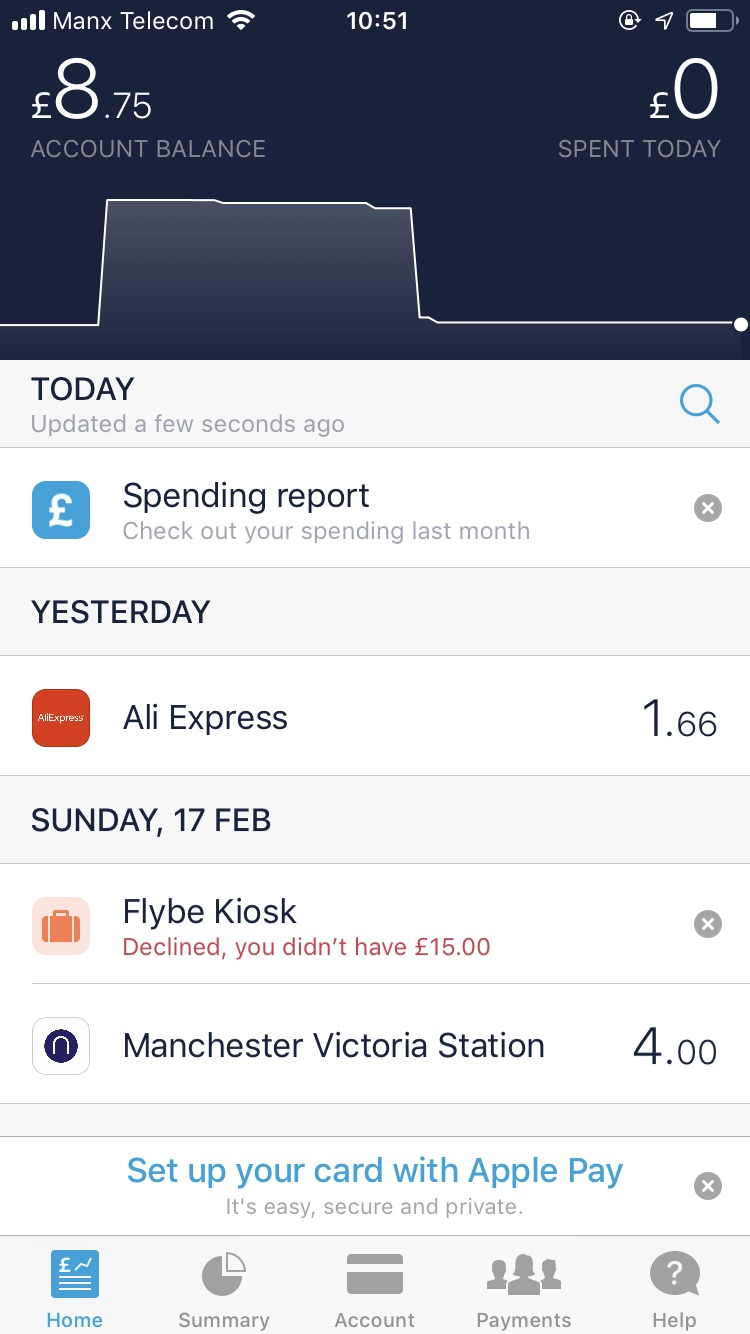

Monzo, a fintech start up approaching Unicorn status, is a Product Management case study in the making. While it is easy to pick successful businesses and look backwards, self-selecting the examples you want to make the case of what you should do, Monzo is the opposite. They are still in the start-up phase and by monitoring their progress you can see how these practices work in the real world. By looking and monitoring Monzo, you can also learn how to differentiate successfully your offering, regardless of the industry.

Truly customer centric

What differentiates Monzo from other tech start-ups is that although they are clearly data driven they are even more customer driven. I became a fan of Monzo’s strategy by starting as a customer and seeing that they were truly customer-centric. Living on the Isle of Man, it is often a challenge working with financial institutions, as we are not part of the UK or EU. While setting up a debit card with one of Monzo’s competitors, Revolut, was an exercise in frustration, Monzo clearly had its team focused on creating a good user experience. Rather than a multi-day response to chats from a CS rep based in a low-cost location (the Revolut model), Monvo offered near real time support as I was trying to navigate setting up from the Isle of Man. This customer focus secured me as a loyal customer – and advocate – at a time when I was looking for a long-term fin partner. Monzo is now my card of choice even though there offering is feature-wise like Revolut. Given the importance of engagement and retention on LTV, this was a wise investment on Monzo’s part.

Product strategy based on making customers life easier

From a product development and management point of view, Monzo is somewhat unique in that it focuses on eliminating friction from customers’ daily life rather than adding a list of features. Monzo sent to its customers a blog post from its CEO about its plans for 2019 and what struck me was that most of the new features they will test were aimed at reducing or eliminating (in Blue Ocean parlance) rather than adding:

- Automatically compare utility options, such as energy providers, so the customer does not have to go to price comparison sites

- A way to get a mortgage or refinance with less paperwork

- Centralizing a customer’s loyalty schemes and reward programs

- Offering different types of insurance without complex terms and conditions

- Help building and tracking a customer’s credit score, as most customers do not know how their credit scores are calculated (and the credit agencies are not transparent)

What is particularly thought-provoking with these features that they are considering is not that they are innovative but that they make the customers’ life easier. They are not trying to be the coolest start-up; I did not see the words AI, crypto or VR anywhere in their roadmap. Instead, Monzo is focused on eliminating hurdles their customers face in their daily lives.

Great FTUE and simple UIUX

Another area where Monzo excels is its first-time user experience (FTUE) and user interface and experience (UIUX). When I first signed up for Monzo, I found its FTUE unique in that they turned a potentially negative experience into a positive and viral moment. When I first applied for Monzo’s debit card, they apparently were experiencing rapid growth and there was a delay in completing the KYC (know your customer) process and delivering physical debit cards. Rather than ask you to endure the delays, thus immediately decreasing your satisfaction, Monzo placed me in a queue with specific information on how many customers were ahead of me and when I would receive my card. They then allowed me to jump ahead by recommending Monzo to friends (which I did), and immediately updating how many people were still ahead of me in the queue. Even before becoming a customer, they turned me into an advocate. They then created a positive feeling by giving me control and visibility into the process.

Beyond the initial experience, Monzo has a very straightforward user interface, it is very easy to navigate and learn how to use the features. You never need a tutorial or help, the product is designed to allow you to determine quickly how to conduct transactions.

Monzo reminds me of Uber, where upon opening the app anyone can figure out how to request a ride. Creating a simple UI, however, is more difficult than creating a complex AI. Any designer can build a UI with 100 options, nested in menu after menu. Reducing those options requires a deep understanding of the customer journey and where the customer is getting value as well as hard decisions on what to include and what to delete.

The UI is also consistent with the product approach described above on making the customers’ life easier rather than just providing them with more options. If the product team simply added feature upon feature, then even the best UI designer would be unable to keep the app’s user interface clean. With alignment between the product and design team, Monzo can focus entirely on removing complications from its customers’ lives.

Lessons

The strategy that Monzo is pursuing provides many useful practices for companies in other parts of the tech space, gaming, gambling, etc. Rather than trying to differentiate yourself from competitors by adding fancy bells and whistles, look at ways you can make your product easier and simpler than competitors (again, more difficult than just adding a new game to your offering). Also, ensure that everything is aligned to your strategy with your customer. If you are trying to provide a fast, clean experience, then not only should the product team develop consistent features, but your support team should focus on creating a complimentary experience and your design team should ensure the app reflects this focus.

Key takeaways

- Monzo, a UK based FinTech start-up, is a future case study in product management best practices. By looking and following Monzo, businesses in other industries can learn how to differentiate their offering.

- Key to Monzo is a product strategy focused on making its customers lives easier rather than adding glitzy features.

- Monzo is successful by aligning its entire business on making a customer’s experience simple, from product features to the first time user experience to the overall user interface through customer support.

The Halo Effect and How to Avoid It

Several months ago, a colleague read and commented on

The Halo Effect by Phil Rosenzweig, and although I have mixed opinions of the book it contains some great lessons on avoiding biases that lead to misjudging the causes of success or failure. Since reading the book, I have extended these ideas to both understand what activities to replicate and how to communicate better cause and effect.

The Halo Effect drives people to over-simplify why a company or product is succeeding, often misattributing it to leadership or a visible initiative. It can lead to negative consequences by driving incorrect hiring and firing decisions or causing incorrect strategic pivots. The Halo Effect is driven by basic psychology, Rosenzweig points out that “social psychologist Eliot Aronson observed that people are not rational beings so much as rationalizing beings. We want explanations. “

The Halo Effect is attributing a company’s success or failure to its leader or a specific strategy or tactic. People may look at a successful company and believe its acquisition or HR strategy is responsible for the success. This belief then becomes common and other companies replicate the strategy but experience different results. The problem is that the success was probably due to many or alternative factors and just copying one, which may or may not have contributed to the success, does not create the same recipe for success. You may actually be copying part of the strategy or leadership that does not work.

It is the same with individuals. If a company is successful, people are quick to credit the CEO. Articles and books are written about the leader but in reality the company was probably successful because of many factors, both external and internal. Not only then are those who copy the behavior of the CEO disappointed with their results, the successful CEO himself may find failure one year later even if they have not changed.

I have seen this issue many times in sports, both in business and other areas. A manager or coach can be brilliant one year and stupid the next. Yet the manager is the same person, with the same philosophy and strategy. Either the previous success was misattributed or the failure is. I remember when Claudio Renieri shocked everyone as Manager of Leicester City when they won the Premier League in 2016, only to be fired the club in 2017.

The reality is that the success is a combination of factors (including luck) and his strategy was not singly responsible for success or failure. This argument is not simply academic, as it impacts who the club hires and releases. Extended to the business world, it impacts who you put in leadership positions, promote or remove.

There are many factors that contribute to the Halo Effect. Most managers do not usually care to review discussions about data validity and methodology and statistical models and probabilities. They prefer explanations that are definitive and offer clear implications for action. They want to explain successes quickly, simply, and with an appealing logic.

There are multiple reasons that the Halo Effect is so widespread. First, it is impossible to experiment or test real life scenarios to determine actual cause and effect. Second, people love a story and the Halo Effect creates a nice (albeit inaccurate) success story. Third, many, including data analysts, mistakenly equate correlation with causality. Fourth, people often neglect to look at the overall ecosystem and try to simplify a situation to a vacuum. They look for one answer when the reality is much more complex. Finally, people often neglect to account fully for the impact of competition.

You can’t experiment to determine business success

When looking for why a company succeeds, you cannot replicate the methodology an app or game developer would use on why a feature works. There is no way to bring the rigor of experimentation to questions like why a company tripled in revenue or experienced a sales decline. If you want to know the best way to manage an acquisition, you cannot buy 100 companies, manage half of them in one way and half in another way, and compare the results. Without the ability to run a statistically significant experiment, people search for other ways to understand success and failure.

Reinforcing this problem is the confirmation bias, since there is not objective data people pull the data that confirms what they believe is the cause. People do not recognize good leadership unless they have signs about company performance from other things that can be assessed more clearly—namely, financial performance. Roswenszweig writes, “and once they have evidence that a company is performing well, they confidently make attributions about a company’s leadership, as well as its culture, its customer focus, and the quality of its people….But when some researchers took a closer look, they found that …the scores … for a given company turn out to be highly correlated—much more than should be the case given variance within each category. Furthermore, many of the scores were very much driven by the company’s financial performance, just what we would expect given the salient and tangible nature of financial results. “ In effect, they back into confirming their original hypothesis on the cause of a success (or failure).

Pick any group of highly successful companies and look backward, relying either on self-reporting or on articles in the business press, and you will find that they are said to have strong cultures, solid values, and a commitment to excellence. This does not prove these cultures are actually strong, but they are viewed as strong due to the company’s success.

People love stories

Marketers have known for a long time, as have entertainment companies, the power of stories. Rather than explaining the features in a pair of runners that would help in a soccer match, a good marketer will explain how the shoes are developed in conjunction with world-class athletes, who then go to the factory to test them. This type of story is much more compelling (even if false) than an objective review of facts. The same problem contributes to the Halo Effect.

People love to hear how the charismatic leader led the company from a start up to a Unicorn. These stories sell books and magazines (or generate web traffic). The tendency to attribute company success to a specific individual is hard to resist. We love stories because they do not simply report disconnected facts but make connections about cause and effect, often giving credit or blame to individuals. As Rosenzweig writes, “our most compelling stories often place people at the center of events. When times are good, we lavish praise and create heroes. When things go bad, we lay blame and create villains. Facts were assembled and shaped to tell the story of the moment, whether it was about great performance or collapsing performance or about rebirth and recovery. “

The book uses the examples of Cisco and ABB to reinforce the point about the power of stories. Both companies were written about in glowing terms, with many trying to replicate the approaches of John Chambers at Cisco and Percy Barnevik at ABB. As long as Cisco was growing and profitable and setting records for its share price, managers and journalists and professors inferred that it had a wonderful ability to listen to its customers, a cohesive corporate culture, and a brilliant strategy. And when the bubble burst, observers were quick to make the opposite attribution. The same happened with ABB, where Barnevik went from revered business leader to scandal plagued miscreant. The reality was neither Chambers nor Barnevik changed, the story changed to fit the new performance.

Equating correlation with causality

One of the most dangerous manifestations of the Halo Effect is equating correlation with causality. While the correlation may be useful for the purposes of suggesting causal hypotheses, it is not a method of scientific proof. A correlation, by itself, explains nothing. Rosenzweig writes, “by looking only at companies that perform well, we can never hope to show what makes them different from companies that perform less well. I call this the Delusion of Connecting the Winning Dots, because if all we compare are successful companies, we can connect the dots any way we want but will never get an accurate picture. “

Companies that consider themselves data driven and even business intelligence teams, often fall into this correlation trap. They start with a success (or failure), either their own or another company, and then dissect it by looking for correlations between the success and a certain activity. Eventually you will find something, even if the correlation is coincidental. If you are starting with a hypothesis, I guarantee you there will be one relationship that “proves” your hypothesis, no matter what you are claiming (and how accurate you are). A good data scientist can even prove a statistica significance to almost anything, they will find some test that “proves” their claim.

I always laugh at the articles written around the World Cup or Super Bowl about how the region or league of the winner will impact an election or economic growth (i.e. if a California team wins the Republicans will win the next election). Obviously, it is just random luck but there is so much activity occurring at any time there will be some correlational relationship. The sporting event, though, is not driving the activity (there is no causality) and is no more likely to predict an up economy as a coin flip would.

People fall into this trap because they are looking for an easy answer. Rather than understanding all the factors that contribute to a drop in registrations in a region, the analytics team will point to a new product introduction that occurred roughly the same time. For them, it is problem solved. Only when their sales continue to fall or extends to other regions do others begin to see that the problem is much more complex.

Single explanations often do not exist

Another issue driving the Halo Effect is that most results are not driven by one factor. So many things contribute to company performance that it is impossible hard to know exactly how much is due to one particular factor. Even if we try to control for many things outside the company we cannot control for all the many different things that go on inside the company.

All of us can probably think of examples that show this phenomenon. In my case, I was once asked during an exit interview why I quit. Rather than one answer, which the interviewer was expecting, it was a series of experiences over a year. There were several triggers but you could not attribute it to any one variable, as much as the HR person was hoping. Another example is when one of our products out-performed projections. While it would have been easy to explain it as one brilliant decision, and that is what the CEO was looking for, it was a combination of product changes, changes with the competition and a platform shift.

Rosenzweig writes, “the new CEO does something—such as setting new objectives, or bringing about a better market focus, which may help improve the corporate culture, or overhauling the approach to managing human resources, and so on. The improved performance we attribute to the CEO almost certainly overlaps with one or more other explanations for company success. Which brings us to the nub of the problem: Every one of these studies looks at a single explanation for firm performance and leaves the others aside. That would be okay if there were no correlation among them, but common sense tells us that many of these factors are likely to be found in the same company.”

The competitive impact